In Part One, Yukinori Shitautsubo talked the challenges of sea urchins and the Japanese seafood industry. Desertification of the oceans is a particularly big problem, and they are experiencing the loss of seaweed, and the quality of sea urchins, a key element of their business, is declining yearly. To break out of that status quo, Mr. Shitautsubo started conducting joint research with Hokkaido University in 2016.

(<<Read Part 1)

In Part Two, we interviewed him about the groundbreaking new technology of restorative sea urchin aquaculture, which promises to increase market value 100-fold and was developed with Hokkaido University and other researchers. His business in Australia which he aims to expand to three locations by 2027,, his thoughts on the Japanese seafood industry as well as vision, and more.

——In Part One, you said that you had begun research and development at Hokkaido University to resolve issues with sea urchins. What have you been developing?

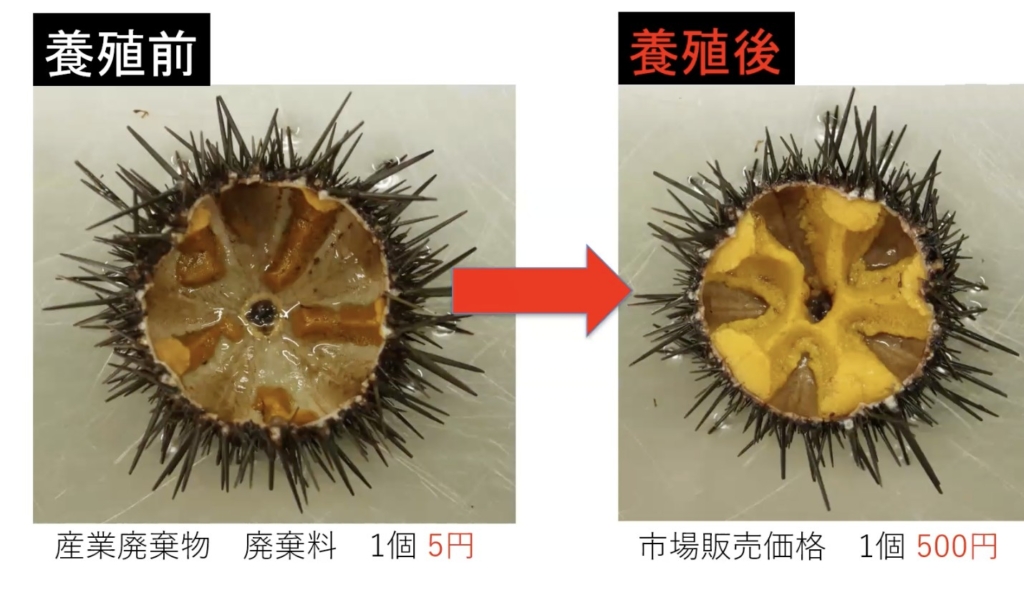

Sea urchins have been declining in meat content with the loss of seaweed that they feed on due to ocean desertification, and they have ended up turning into a “nuisance of the sea” in the desertified areas of the ocean where they live, as suggested by the “urchin” in “sea urchin.” Hoping to turn that situation somehow around, we developed the sea urchin feed Hagukumu-Tane in cooperation with Hokkaido University, and we have also patented it. Feeding sea urchins with this seaweed substitute results in rapid enlargement of the edible portion (gonads), increasing meat content and bringing them to a level where they can be shipped. Once sea urchins have been left for a long time in a desertified area, remaining for a long time in a state of starvation, even eating kombu or other seaweeds will no longer improve their meat content, and they also lose their color. But feeding them with Hagukumu-Tane improves meat content as well as color and flavor. We are now able to produce as much as 100 times more value in about 2 months.

Restorative sea urchin aquaculture using Hagukumu-Tane takes place in a farm, as pictured below. This example is in Yakumo, Hokkaido, and while Uchiura Bay, which lies off Yakumo, is a major production center for scallops, long years of aquaculture led to a buildup of feces on the seafloor, and the scallops were dying. We, therefore, gathered up meat-poor Ezo bafun sea urchins present in large quantities on the desertified seafloor and started conducting Hagukumu-Tane-based restorative aquaculture. We are raising and shipping previously totally unmarketable, meat-poor sea urchins. In the meantime, seaweed is also gradually coming back. This is truly sustainable seafood. With highly motivated participation from young local fishermen who support these efforts as well as government support, the initiative is set to last.

In September 2022, this project won in the Crafted Catapult category at the ICC (Industry Co-Creation) Summit Kyoto 2022, which featured over 300 top leaders active at the forefront. That gave me an opportunity to fly to Tasmania, Australia, in February 2023 because I had read the book Blue Carbon, where I learned that 70% of the world’s seaweed was in the ocean around Australia, and 95% had been lost due to sea urchins. Unable to believe it, I went to the actual location, which was an obvious fact.

——Is that what led you to set up a local company in Australia?

Yes. In Tasmania, I had the opportunity to give a presentation on the importance of restorative sea urchin aquaculture and seaweed bed restoration at a conference held by the Fisheries Research and Development Corporation (FRDC), which brought together about 150 sea urchin researchers from around the world. State governments and others approached me about trying out this project in Australia, too. In order to solve the problem of sea urchins and seaweed in Australia, we set up KSF Australia (Kita-Sanriku Factory Australia) in Melbourne, Victoria. We are also planning to start a business at the end of this year with the aim of creating a circular industry by making sea urchin feed out of unused stocks of the red algae Asparagopsis taxiformis which is grown locally and is apparently able to cut methane gas by over 95% when mixed with cattle fodder.

Moreover, because sea urchin is rich in folic acid even for seafood, we are also carrying out research and development with Japanese researchers with a view toward a project to create supplements out of sea urchin species that are unpalatable and therefore not suitable for use in food. In Australia, we also plan to expand our business beyond Melbourne to Sydney and Tasmania by 2027. My mission today is taking on the “UNI is Universal Agenda” (“uni” is Japanese for “sea urchin”) to resolve the challenges involved with sea urchins in Japan and around the world.

——Are you planning to shift your future business entirely to Australia?

With the business in Australia, I hope to build up a track record by around 2030 and pass the baton to a colleague to take over for me, aiming to leverage that success as a precedent for Japan. Then, I intend to devote myself once again to the seafood industry of my native Sanriku. I will shift new value and assets gained in my Australian business to the seafood industry in my home region of Sanriku. Instead of struggling amidst the immense difficulty of changing the Japanese seafood industry, my vision is to set my sights on the future, first scaling up Japanese technology as much as possible abroad then coming back to Japan to reinvest in the local seafood industry.

——Tell us your opinion about the Japanese seafood industry. What should Japanese seafood producers, distributors, and retailers do for the future of the Japanese fishing industry?

For example, local Japanese supermarkets have hardly any fish from the region, and they are selling instead, say, Chilean salmon, Maltese tuna, and other products produced abroad. People cannot buy local fish in their region; even if they can, it is cheap fish, while the high-quality fish gets sent out of the country. Moreover, it seems to me that the Japanese seafood industry will only have a future if Japanese seafood producers, distributors, and retailers clearly convey the appeal as well as story and background of Japan’s producing regions to people going about their lives (consumers), creating a cycle where people going about their lives (consumers) sense the value and buy the products. The most important thing in that regard, I believe, is the developing the traceability system.

——I hear you also participate in the Seafood Working Group of the Cabinet Office’s Council for Promotion of Regulatory Reform.

Yes. In this working group, I put forward a vision of the ideal fishing village region. I would also like people at the Fisheries agency to look at the situation on the ground and think about the future of fishing villages from a local perspective. However, as they might, the government cannot change things overnight. On the other hand, change via the market requires success stories, and in reality, that is tough for Japan.

Even if we try to make a difference in the Japanese seafood industry, I think it is a problem that there are too many stakeholders. Whatever interactions we might have with the Fisheries Cooperative, there is also involvement by organizations like the Federation of Fisheries Cooperatives, the Fisheries Agency, and the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries. Meanwhile, there are very few stakeholders in Australia, and each state government has the power to make decisions. We need to seriously think about how to set up an environment where innovation happens easily.

——Tell us about the source of your passion to change the Japanese seafood industry through a global approach.

I know of a past when Japanese seas were bountiful, and the seafood industry was prosperous. I intend to devote myself to bringing that back. I want to give the children who will carry forward the next generation an environment where the seas are productive, workforce shortages are addressed by progress in digital transformation, and people can work in the seafood industry with pride. That may no longer be possible for my generation, but perhaps in my son’s or grandchildren’s generation, they will be able to bring about a bountiful sea where working in the local seafood industry seems like a good option. I will go forward in order to realize such a future.

Yukinori Shitautsubo

Born 1980 in Hirono, Iwate Prefecture. After graduating from university, I worked for a car dealer and life insurance company, then returned home. Started local seafood venture Hironoya Co. Ltd. in 2010. Soon after, Hirono was hit hard by the Great East Japan Earthquake. Set up strategic subsidiary Kita-Sanriku Factory Co. Ltd. in 2018 with the mission of creating a new future for the region and the seafood industry. Further, set up a local subsidiary in Melbourne, Australia, in 2023, expanding restorative aquaculture horizontally beyond Japan as a global company. 100 Japanese Breakout Achievers in Asahi Shimbun Publications magazine Aera (2014). 300 Outstanding Small and Medium Enterprises (2016). Companies Driving Regional Growth (2018). Tohoku New Business Council’s Tohoku Entrepreneur Award (2021). 3rd Place in ICC Summit Fukuoka 2023 Catapult Grand Prix (2023).

Original Japanese text: Shino Kawasaki

-1024x606.png)

_-1024x606.png)

1_修正524-1024x606.png)

.2-1024x606.png)

2-1024x606.png)

-1-1024x606.png)

Part2-1024x606.png)

Part1-1024x606.png)