It has been four months since the Act on Ensuring the Proper Domestic Distribution and Importation of Specified Aquatic Animals and Plants (hereafter, “Fishery Products Distribution Act”) came into effect in December 2022. In Part One, Fisheries Agency Processing Industries and Marketing Division Director Maiko Igarashi recalled her experiences reconciling the views of stakeholders at planning committee the like, and I asked her about the new system’s operational status with regard to Specified Class I.

In Part Two, we mainly discuss negotiation and cooperation with foreign countries regarding Specified Class II, and I also ask Maiko about her own past and future ambitions.

――What is the operational situation like with regard to Specified Class II fishery products (Pacific saury, squid, mackerel, and sardine)?

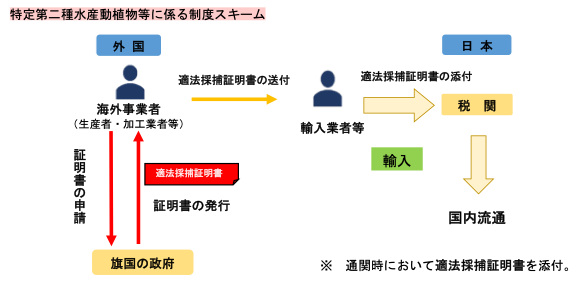

Specified Class II requires the inclusion, when importing from a foreign country, of a certificate issued by a foreign government saying that the product was harvested legally. In fact, the majority of imports are processed goods such as frozen goods, so inclusion of certificates for products harvested after the law went into effect just started stepping up recently.

We conduct bilateral negotiations to have countries issue the proper certificates, and we are continuing our negotiations with countries where negotiations have not yet been completed. Even with countries where negotiations are finished, issuance is taking place amid ongoing fine-tuning of system operations. So it is a bit of a work in progress, but in my current assessment, it looks like we were able to introduce the system without any significant disruptions overall.

――What kind of bilateral negotiations do you have regarding Legal Harvest Certificates?

The most important thing is to check whether that country has a framework and mechanisms in place to verify legal harvesting and properly issue certificates, and then, whether or not they have legal structures for fisheries management comparable to our Fisheries Act or Fishery Products Distribution Act.

――I expect that systems differ widely by country. Are there countries that do not meet the certification standards demanded by Japan’s Fishery Products Distribution Act?

Such countries would obviously not be approved right away. The approval process ensures that imports can take place only after we have been able to ascertain legal structures and a system capable of well-corroborated validation of the certification requirements.

――How many countries have finished bilateral negotiations and are now issuing certification documents?

If we include “regions” like the EU, there are 35 countries and regions as of April 1st (2023). We began negotiations with countries where we have a significant record of past imports, so we have already been able to cover about 96% of the value of past imports of Specified Class II to our country, and in that sense, there should be no impediments to importation.

――Some people are skeptical about the reliability of information recorded in Legal Harvest Certificates and Processing Declarations issued by many countries. Are there any mechanisms to guarantee reliability?

We never have those concrete facts that we heard of such voice as of this time. Again, our process ensures that importation is allowed only after we have given our approval, provided that we have been able to ascertain at the bilateral negotiations stage whether or not that country’s government has in place a framework and mechanisms capable of properly verifying legal harvesting as well as appropriate legal structures and enforcement procedures for fisheries management.

Simply put, the certificates are issued by foreign governments, so if a situation were to arise in which their reliability were doubtful, then we would take swift action with respect to the government that issued the certificates.

――If countries have inconsistent policies, it seems like it would be quite burdensome for exporters to comply with each of the various systems. Has there been progress on international cooperation toward unifying the systems?

Like you say, I think it is important for the major market economies of Japan, the EU, and the US to act in concert on trade-related regulations. The Japanese regulations in the area of Specified Class II imports are modeled on the EU’s catch certification system. This is because the EU system has a 13-year track record as of this year since its introduction, and it is widely accepted by over 90 countries. If we are consistent with that system, then we can trade smoothly.

On the other hand, there are also areas where circumstances differ by country, so in such cases I believe it is still necessary to give careful consideration to practicability on the basis of actual conditions such as the logic of the regulations, burden on staff, and the like.

――The goal of the Fishery Products Distribution Act is to conserve resources in a sustainable way, and although you have emphasized the need to move forward on that, were there also discussions at the planning committee on, for example, human rights issues?

IUU fishing, as mentioned in the preceding US and EU laws corresponding to our Fishery Products Distribution Act, did not include the concept of “human rights,” so no particular discussions of that nature took place in the planning committee at the time.

――Concerns have recently been growing on the problem of human rights violations such as slave labor on fishing vessels. Even if fishery products were to be imported after possibly being caught with slave labor, ordinary consumers would not be able to tell the difference. Does the current Fishery Products Distribution Act account for that?

Human rights issues like forced labor are a matter not just for the Fishery Products Distribution Act but include a variety of recent cases and problems such as, for example, forced labor of Uyghurs with respect to clothing made by Japanese manufacturers. The US uses customs law to ban imports not only of fishery products but of all products connected with forced labor, and the EU is likewise working to introduce regulation banning trade in goods involving forced labor.

In Japan, too, I think it is a question of how we go about dealing with the issue of human rights violations as a nation overall. In recent moves, deliberation is progressing not only for fishery products but for the country as a whole, including the formulation of guidelines to ensure respect for human rights so that companies do not deal in such products, based on discussions at an investigative commission set up by the Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry.

Ms. Igarashi speaking at Tokyo Sustainable Seafood Summit 2022

Ms. Igarashi speaking at Tokyo Sustainable Seafood Summit 2022

――Have you wanted to become a civil servant since your student days?

I spent three and a half years in Washington, D.C., in the US at an impressionable time. It was a very special city. We even had a class in middle school on the subject of government policy and policy makers. It was the type of place where locals would instantly switch back and forth between the Democratic and Republican parties whenever the administration changed.

So, I had a vague idea, rather intimately felt, that “To be a policy maker is to do good in the world. I want to be a policy maker.” I also had the desire to contribute to Japan, domestically, rather than contributing internationally, so I wanted to work for the national government.

――In that regard, was the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries also your own choice?

It was. I think that eating is the most important thing for survival, and I was interested in international relations and environmental issues in my student days, so the MAFF seemed to be the office where I would be able to work in those two areas, yes.

――Why did you go to the US to study more law in your fourth year at the Ministry?

I may have a background studying law at university, but as you might expect, being in government can involve lawmaking, and we approach our work in accordance with the law, so legal thinking is demanded every day. I therefore chose law as my specialty while studying overseas as well. Upon returning to the MAFF after studying in the US, I went on assignment to the Secretariat of the Basel Convention in Switzerland and gained experience doing legal work alongside British lawyers under the title Associate Legal Officer.

――I expect that your considerable international experience was also put to good use in negotiations and cooperation with various countries on enforcement of the Fishery Products Distribution Act. You were also shuffled around to various posts within Japan while continuing your duties at the MAFF as a working mother. How do you make use of that experience in your current work?

Compared to my older coworkers who paved the way in the previous generation, with a system of parental leave in place by the time I started at the Ministry, I think we now have an environment where it is possible to combine work and child rearing. There is also support for families, and so I have been able to continue working to date.

I had many opportunities to handle relatively “downstream” administration at the MAFF. The same was true when I was assigned to the Food Labeling Planning Division at the Consumer Affairs Agency, and the Food Quality Division, Wood Utilization Division, Japanese Food Office, and the like also involved downstream administration close to the consumer. The Processing Industries and Marketing Division where I am now also has jurisdiction from processing to distribution and consumption, and within that context, the Fishery Products Distribution Act is a law targeting such distribution with the major goal of sustainable utilization of fishery resources, so I think my experience in downstream administration has likely been of use.

――You launched “Fish Days”* last year at the Processing Industries and Marketing Division. Is that also continuing to gain in popularity?

That just started in October, two months before we were to begin enforcement of the Fishery Products Distribution Act, but I think we were able to get it off to a good start. It is a public-private partnership which now has over 700 supporting members, including not only fishery operators but a variety of others in retail and food services as well as hobby fishing and the media. We also got Sakana-kun to become the Fish Days ambassador.

I want Fish Days to become established for many years to come, so I am hoping to promote initiatives during Fish Days alongside private companies and organizations to appeal to the public by coming up with different ideas every year.

――Are you also doing things at home?

I’m doing my best to get my kids to eat fish [laughs].

――Having become the policy maker that you envisioned in your student days and taken part in national administration, how have your current efforts in fisheries administration affected you?

The Fishery Products Distribution Act was really the first attempt to introduce genuine regulation on the distribution of fishery products themselves, so it was quite a big task, but I feel honored that I was able to supervise it.

Designing the system was tough, but where I really felt the strain was in the imposition of regulation on fishery operators and distributors, each of whom plays a role in supplying everyone in the nation with fish daily. It was very challenging to get their agreement while taking care not to unreasonably impede the legitimate business that they are so proud of, and I have struggled with getting the balance right.

In that sense, I am glad that we were able to move into enforcement without problems, and I feel a sense of accomplishment at having taken part in such a big job.

――What kind of endeavors do you have in mind for the future?

I intend to stay on course within the domain of the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries. I am currently at the Processing Industries and Marketing Division, so the most important thing is getting fish to everyone’s table on a consistent basis. The fact is, for a stable supply of fishery products, it is not just the catch but also the processing, distribution, and delivery to consumers that are absolutely crucial.

Processing and distribution sectors which play important role in stable supply of fishery products (Photo source: Fisheries Agency)

Processing and distribution sectors which play important role in stable supply of fishery products (Photo source: Fisheries Agency)

The role I was given is in the processing industries and marketing field, so I will do my best at that. We have a lot of small and medium-sized businesses, so I will work hard to support them, and with consumption still falling domestically, I hope to be able to contribute to increased consumption of fishery products as well.

Maiko Igarashi

Graduated from Waseda University (Faculty of Law) in 1997 and joined the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries in the same year. Was assigned to the Livestock Industry Bureau, Food and Marketing Bureau, and United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) as well as the Minister’s Secretariat, International Affairs Department, and Forestry Agency before becoming the Head of the Food Culture & Market Expansion Division (Japanese Food Section) in the Food Industry Affairs Bureau. Became the Director of the Food Labeling Planning Division at the Consumer Affairs Agency in August 2019. Assumed current post in July 2021. After acquiring her Master of Laws degree(LL.M.) from Harvard Law School, she became a registered lawyer in the State of New York.

Original Japanese text: Chiho Iuchi

-1024x606.png)

_-1024x606.png)

1_修正524-1024x606.png)

.2-1024x606.png)

2-1024x606.png)

-1-1024x606.png)

Part2-1024x606.png)

Part1-1024x606.png)