Part1-1024x606.png)

According to Fish to 2030: Prospects for Fisheries and Aquaculture*1, a report published by the World Bank in 2013, the total global production of fish is expected to grow by 23.6% between 2010 and 2030. However, while many countries and regions, such as India, China, and various other Asian countries, are considered to have high potential to turn fisheries into a growth industry, Japan’s fishing industry is expected to dip into negative growth of minus 9.0%.

In fact, according to The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture (SOFIA) (published by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations), the global food fish production increased from 123.8 million tons*2 in 2009 to 156.4 million tons*3 in 2018. Over ten years, production increased by 26%.

Meanwhile, fish production in Japan in 2020 was 4.17 million tons*4, a decrease of 0.5% year-over-year. It marked a second consecutive year of lowest production*5 since comparable data became available in 1956, indicating an unusual situation even from a global perspective.

Why did the Japanese fishing industry, which used to lead the world until the 1970s, turn into an ailing industry? We spoke to Dr. Toshio Katsukawa, an associate professor in the Office of Liaison and Cooperative Research at the Tokyo University of Marine Science and Technology. Ever since he was in graduate school in the 1990s, Professor Katsukawa has been sounding alarm bells, based on data, and calling for the need to reform Japan’s fishing industry.

Toshio Katsukawa

Born in Tokyo in 1972, Toshio Katsukawa graduated from the Department of Fisheries, Faculty of Agriculture, The University of Tokyo, and he has a phD in Agriculture. After serving as Assistant Professor at the Atmosphere and Ocean Research Institute, The University of Tokyo, and Associate Professor at the Faculty of Bioresources, Mie University, he was appointed as Associate Professor at the Office of Liaison and Cooperative Research, Tokyo University of Marine Science and Technology, in April 2015. He has continued to engage in efforts to make fisheries a growing industry while traveling around Japan and abroad. Katsukawa is a recipient of the Encouragement Award and the Dissertation Award from the Japanese Society of Fisheries Science (JSFS). His major publications include Japan’s Fisheries Industry Problem (NTT Publishing) and The Day We Will No Longer Be Able to Eat Fish (Shogakukan Shinsho). He is a board member of the Association for Sustainable Seafood for the Future.

— In the past, some countries had overfished and reduced their resources so much that fisheries were close to collapsing. How were they able to reform their fisheries to sustainable and highly profitable industries?

Before the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) was established, the “principle of freedom of the high seas” allowed foreign ships to come so close to the shore of other countries that people could see them from land. Since it was an era that allowed them to fish as much as they wanted, there was no way to prevent overfishing by other countries. Therefore, it was impossible to manage the fishery resources of one’s country.

In 1982, the UNCLOS established the 200-nautical-mile (370 km) exclusive economic zones (EEZ), which allowed coastal nations to initiate stock management. Rational countries with foresight like Norway and New Zealand switched to a new system of managing their fishery resources.

Even in these countries, fishermen objected when fishing regulations were first introduced. But once the regulations were in place, fish began to increase and fishing became profitable. Now, most fishermen support stock management.

— On the other hand, Japan has a history of supporting national policies aimed at developing fishing grounds abroad, upsizing fishing vessels, and enhancing refrigeration and freezing technologies to sustain its overfishing practices as means of increasing food production amid severe food shortages during the postwar period. Why have these policies remained even though the times have changed ?

Japan lacks a culture of taking structural problems seriously and making the necessary changes in a proactive way. We have instead devoted our efforts to prolonging the lifespan of the existing framework through every means possible. This procrastination can be observed not only in the seafood industry but also in our pension system. It is apparent from Japan’s declining birthrate and aging population that urgent action needs to be taken, but we have been putting off changes that are inconvenient.

The same can be said of consumers. In many countries, stock management systems were initially introduced by their political leaders despite resistance from the industry, but this would not have been possible in the absence of public support for catch reduction and protecting fishery resources.

It has been a long time since the subject of declining fishery resources has emerged, but Japanese consumers still have the mindset of “let’s eat more now before prices go up.”

— Are public awareness campaigns effective in transforming how consumers think?

When tackling social issues, it is always important for us to be aware that we are also part of the problem. Many Japanese people believe that the decline in fishery resources is caused by overfishing by foreign vessels and global warming, and that they have nothing to do with it. Even those who recognize that Japan’s fisheries have a role to play view it as a problem to do with fishermen or the government but not with the consumers themselves.

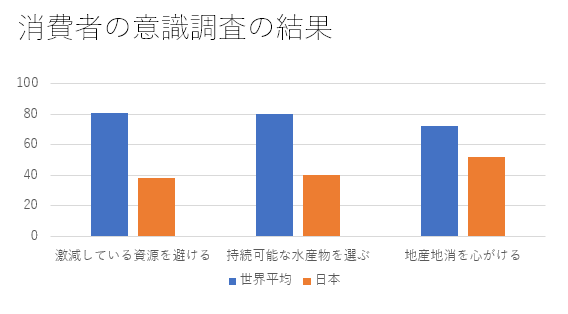

The results of a survey on global consumer awareness of the sustainability of fishery resources are available on the Internet. What is interesting is how they show that awareness of sustainable consumption behavior among Japanese consumers is exceptionally low by global standards.*6

For instance, Japan has the lowest percentage of consumers among the many countries in the world who think that biological resources that are in drastic decline should not be consumed. Only 40% of Japanese consumers think that we should consume sustainable seafood. In comparison, this figure is around 70% even in Russia, the country with the second-lowest percentage after Japan. The percentage of Japanese consumers who make an effort to support local production for local consumption initiatives is also the lowest in the world.

The reason why we have become so different from the rest of the world is likely because of our education. Japanese education on fish consumption tells children that eating a lot of fish is a good thing. However, it may be more appropriate to call such “education” sales promotion if all we tell children is to eat a lot of fish without imparting to them any knowledge of sustainability.

There is a complementary relationship between overfishing and consumption practices that ignore sustainability concerns and focus only on maximizing consumption volume at low prices. Indeed, advocates of such consumption practices include fisheries that also ignore sustainability concerns. Japanese eel (unagi) is the worst example.

Japanese eel used to be enjoyed for special occasions during the Showa era.

Japanese eel used to be enjoyed for special occasions during the Showa era.

—You have pointed out repeatedly in your books such as Gyogyō to iu Nihon no kadai (Japan’s Fisheries Industry Problem) and in various articles that there are three essential steps to take to avoid overfishing and maintain the productivity of our fisheries industry, specifically, (1) understanding the natural production capacity of species in a scientific manner (stock assessments), (2) limiting catch within this production capacity (practicable regulations), and (3) adding value to fishery products (marketing). Can you elaborate on them?

Basically, only species that have the ability to survive in the current environment can continue to exist. This means that species that would naturally go extinct would already have been eliminated. Therefore, there are no sustainability concerns as long as living creatures are caught within the range of their capacity to proliferate as a species.

Today, many fisheries have greatly exceeded the production capacity of species, so we need to significantly reduce our catch from what it is currently. On the other hand, if the number of fishermen starts to decline as a result of this, neither our fisheries industry nor our fish consumption will be sustainable. It is thus imperative for us to find a way to strike a balance between the sustainability of our fishery resources and the sustainability of our fisheries industry.

—How are fish stock assessments conducted in Japan?

Broadly speaking, there are two methods of conducting stock assessments.

One method is based on catch statistics, with the idea that if the fish population declines by 50%, the number of fish caught each time the net is reeled in will probably also be halved. The other method is through experimental operations conducted by research vessels that are independent of the fishing industry. More recently, surveys have also been conducted using high-performance fish finders.

The performance of fish finders has improved in recent times, making it possible for fish populations in the ocean to be determined more accurately. However, populations of fish that do not swim in schools cannot be monitored by fish finders. Also, fishermen these days have fishing equipment with better performance, so they can locate schools of fish and catch them more efficiently even when their populations are declining. In particular, the catch tends to be stable until the fish is truly gone when a species is caught in its spawning grounds where adult fish gather during the spawning season, which makes this method an unreliable indicator of a species’ true population.

Since both methods have their inherent inaccuracies, experts often utilize a combination of various methods to make estimates. However, there are also many different ways to interpret and handle data, and it would not be an exaggeration to say that if 100 experts were given the same data to make their estimates, they will produce 100 different sets of results.

When uncertainty is so great, it is vital to take a cautious action. This is because fish that is not caught this year may be caught next year, but fish caught this year cannot be returned to the ocean. In the face of insufficient information, we should be more conservative and increase a fishing quota only after confirming that the fish population is healthy.

Unfortunately, this is not how fishing quotas currently work in Japan. If someone is told by fishermen to make it look like there is enough fish because they want to catch more fish, that person can easily make the numbers larger by changing the parameters. With so much pressure on scientists on top of the great uncertainty, the results of stock assessments can be easily distorted.

Dr. Katsukawa speaks at the Tokyo Sustainable Seafood Symposium 2019

Dr. Katsukawa speaks at the Tokyo Sustainable Seafood Symposium 2019

—In other words, the issue here is the independence of stock assessments.

That’s right. For instance, the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES) brings together researchers from all over Europe to discuss issues based on the same data. This system makes it difficult to distort the results of stock assessments according to the intention of particular countries.

In the case of Japan, the close relations between the seafood industry, the government, and researchers make it more likely for the final results to reflect the wishes of the fishing industry, for better or worse. As a result of this, we still lack an adequate framework for fishing regulations to this day.

*1 FISH TO 2030 Prospects for Fisheries and Aquaculture (The World Bank, 2013)

*2 The State of World Fish and Aquaculture (FAO, 016)

*3 The State of World Fish and Aquaculture (FAO, 2020)

*4 2020 Production Statistics for Fisheries and Aquaculture (Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, 2021)

*5 From “Production Statistics for Fisheries and Aquaculture (Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries)

*6 Global attitudes about sustainable fishing and policies to curb overfishing (Ipsos, 2019)

-1024x606.png)

_-1024x606.png)

1_修正524-1024x606.png)

.2-1024x606.png)

2-1024x606.png)

-1-1024x606.png)

Part2-1024x606.png)

Part1-1024x606.png)