In September 2023, the Task Force on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD) officially released its recommendations in v1.0 of the group’s framework. This news was very relevant for the fisheries industry, which is based on the natural capital of seafood.

Hirotaka Hideshima, who took the stage at the Tokyo Sustainable Seafood Summit 2023 (TSSS 2023), joined Norinchukin Bank in 2021 after working at the Bank of Japan for 32 years. He was selected as a member of the TNFD in November 2022, where he contributed to the publication of the final recommendations.

At the beginning of 2024, Mr. Hideshima and Wakao Hanaoka, CEO of Seafood Legacy, which aims to “pass on the legacy of the ocean to the future,” discussed the future of fisheries from the financial world’s perspective. In part one, we asked Mr. Hideshima about his history and what was going on behind the release of the TNFD’s final recommendations.

Hirotaka Hideshima

Joined The Bank of Japan in 1989. Joined The Norinchukin Bank in April 2021. Of the 32 years at the Bank of Japan, worked in the area of the Basel Committee on Banking Supurvison(BCBS) for a total of 15 years. Worked at the Secretariat of The BCBS(2002-2005), Co-Chaired the Definition of Capital Working Group, Co-Chaired the Macrprudential Supervision Group(MPG), and has been a member of the Committee.

Wakao Hanaoka

Born in Yamanashi Prefecture in 1977 and raised in Singapore from a young age. After graduating from the Florida Institute of Technology’s Department of Ocean Engineering and Marine Sciences, he worked on marine conservation projects in the Maldives and Malaysia. In 2007, he began working at the international environmental NGO “Greenpeace Japan,” where he served as the head of marine ecosystems and as a campaign manager. In July 2015, he went independent and established Seafood Legacy, becoming its CEO. He connects both domestic and foreign businesses, NGOs, governments, policymakers, academia, the media, and a diverse array of other stakeholders to work toward the design of local solutions suited to the environment of Japan and based on international standards.

Hanaoka: You’ve been in the financial world for quite some time, but what made you decide to work at a bank?

Hideshima: I thought that the financial industry would be the best place for me to interact with and learn about a wide range of industries. Industrial structure changes with the times, although no one knows which industries will become the stars of each new era, I thought that joining a financial institution would allow me to connect with the industries that would do just that. I didn’t think I would be able to find them on my own.

Hanaoka: I see. You decided to put yourself in a position where you could cast your net to catch those star industries. In unstable times such as these, when industries and the economy as a whole cannot grow without proper risk hedging, the meaning of the word “star” is changing too.

Hideshima: Disclosure related to risks and opportunities is included in the TNFD, and I am sometimes asked, “What sort of opportunities are out there?” It’s great if you can find them by yourself, but if you’re like me and can’t do that, one possibility is to cast your net over all types of industries, especially in today’s uncertain world. It’s important to cast out your net and be sure not to miss an area where there could be opportunities.

Mr. Hideshima worked at the Bank of Japan for 32 years, joined Norinchukin Bank,

Mr. Hideshima worked at the Bank of Japan for 32 years, joined Norinchukin Bank,

Hanaoka: After entering the financial world and working at the Bank of Japan for 32 years, what made you decide to join Norinchukin Bank? Also, what sort of organization is Norinchukin Bank?

Hideshima: While I was at the Bank of Japan, I worked with the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision* (BCBS) for quite some time. The BCBS discusses what sort of international regulations to make for banks around the world, and Norinchukin Bank is subject to those regulations. Due to my experience at BCBS, I thought I would be capable of assisting the bank in dealing with regulations. I was also interested in how the committee’s discussions would develop.

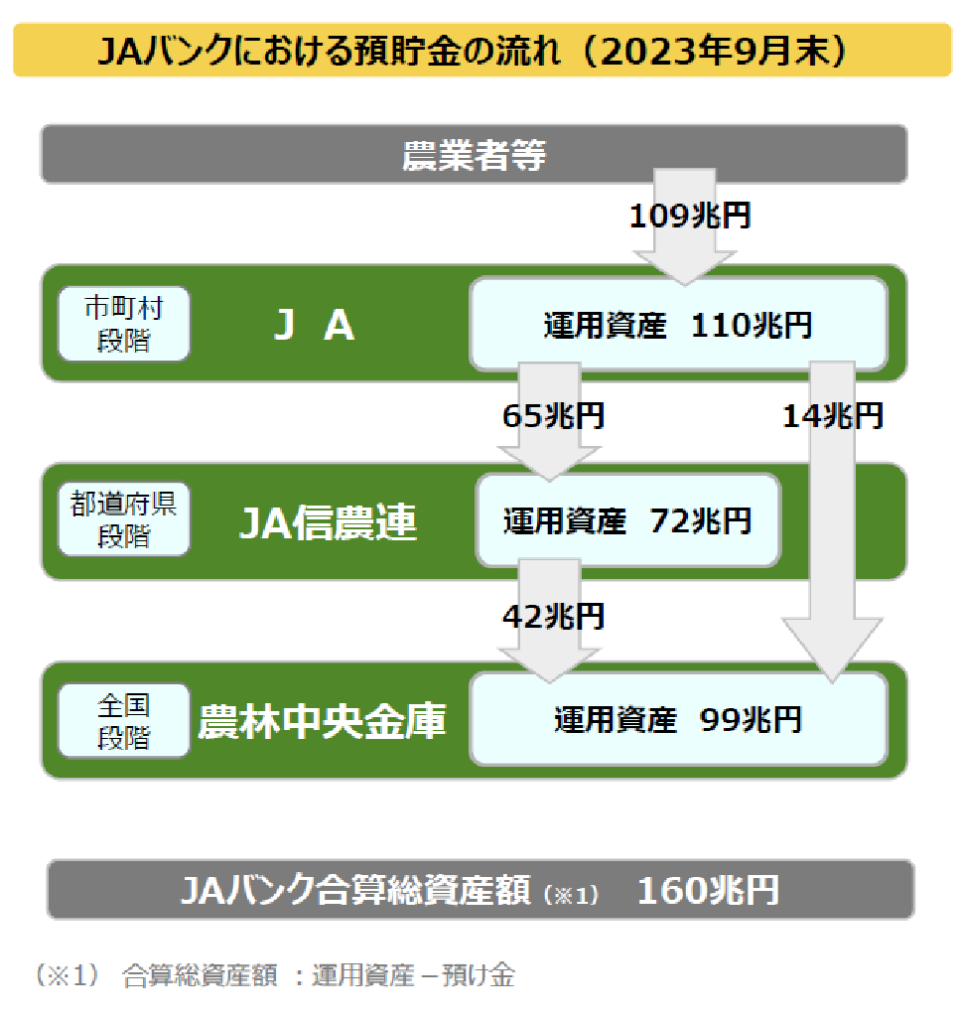

Allow me to explain Norinchukin Bank’s main business. What we do is receive funds from fishery cooperatives, agricultural cooperatives, and prefectural-level credit federations of agricultural and fisheries cooperatives (CFACs/CFFCs), invest those funds in securities like government bonds or loans to large companies, and return the proceeds to our investors.

So, the Norinchukin Bank doesn’t make requests of fishery cooperatives and agricultural cooperatives regarding their activities; actually, we’re the ones who receive requests. Together, fishery and agricultural cooperatives, CFACs/CFFCs, and Norinchukin Bank form the financial institutions known as JA Bank and JF Marine Bank. Each party discusses their direction for the future and invests in the production of a system that benefits the industry.

Hanaoka: From that, it means that if the primary industries have an increased awareness of sustainability, then a support system for it could be created. If they don’t, however, it would be difficult for you to move forward on one. While sustainability measures are advancing at mega banks, do you feel there are gaps between banks and industries?

Hideshima: I believe so. I feel that people closer to the worksite have a stronger desire to maintain the status quo. I think our role is to convey the message that if you don’t change, you won’t be supported in the future, and changing is in everyone’s benefit.

On environmental issues, the phrase “tragedy of the commons” comes up quite often. This means that if a field belongs to everyone and everyone follows the rules, there will be enough grass to go around, and cattle can be raised. However, if everyone tries to get more and more cattle to maximize profits, then the grass will be eaten away. For both the fisheries and agriculture industries, I believe that cooperatives such as JA Bank and JF Marine Bank could be one solution.

Hanaoka: You’re saying that maintaining capitalism as a healthy form of economic competition will require the entire industry to work together to protect the commons, which is part of their capital resources, or else the very foundation of their competition will be lost. One could say that trying to claim for ourselves what we should be working together to protect describes the history of overfishing.

Hanaoka: You were selected as one of two Japanese members on the TNFD in November 2022. How did you feel when you were selected as a member? Also, as a member, what kind of role do you think is required of you?

Hideshima: TNFD launched with 34 members in 2021. Then, in 2022, there was an announcement that they would be bringing in more members, and I applied as a candidate from Norinchukin Bank to contribute to the development of the framework from the perspective of a financial institution based on the agriculture, forestry, and fisheries industries. I heard that there were many applicants, though, so I didn’t get my hopes up and didn’t think too deeply about what I would do if I became a member. So, when I did get selected, I was honestly thinking, “I’m in big trouble now.”

You see, I had never been involved in sustainability at that point. I studied the subject while participating in the TNFD working group by reading the literature and talking to people who are familiar with sustainability. I also learned from the other Japanese member of TNFD, Makoto Haraguchi of MS&AD Insurance Group Holdings.

The drafting of the final recommendations started at the same time I became a member, but there were already many environmental experts on the team, and projects were underway in cooperation with various research institutes. As such, I was more focused on contributing to discussions surrounding guidance for disclosure, procedures, and processes than the content of the framework itself.

Since I joined the task force midway, I would often express my opinion only to be told that they’d already discussed it. Still, I continued to give my opinions, intending to perform a double-check with a new perspective. I was still a newcomer to sustainability, so it was my hope to contribute by making the guidance for disclosure easy to understand, even for beginners.

——

Original Japanese text: Shino Kawasaki

-1024x606.png)

_-1024x606.png)

1_修正524-1024x606.png)

.2-1024x606.png)

2-1024x606.png)

-1-1024x606.png)

Part2-1024x606.png)

Part1-1024x606.png)