The Fisheries Agency is striving to reform fisheries policy to properly manage fishery resources while revitalizing the fisheries industry, improving the income of fishermen, and ensuring a fishing industry workforce with a balanced age distribution. To support this, amendments to the Fisheries Act (Revised Fisheries Act) were enforced in December 2020, and the Act on Ensuring the Proper Domestic Distribution and Importation of Specified Aquatic Animals and Plants was enforced in December 2022.

Takashi Koya is the standard bearer for reforms as Director-General of the Fisheries Agency, while Wakao Hanaoka has explored the seafood industry as the leader of a social venture seeking rich and sustainable oceans. The two have built a mutual trust despite the gulf between their positions and following the discussion of their vision for fisheries reforms in Part 1, they discuss the stock management to achieve this vision, challenges in distribution, and the outlook for the future.

Hanaoka: You gave a presentation at the Tokyo Sustainable Seafood Summit (TSSS) 2022 about a V-shaped recovery for the ocean and the seafood industry. You said that fish stocks will recover if properly managed.

Koya: There are various arguments. Some say that things will never go back to the way they were because of large-scale land reclamation projects, but all the major land reclamation ended over 30 years ago. Even though it has been more than 30 years, doesn’t it seem strange that fish stocks have still been decreasing the whole time? And while some might blame foreign fishing boats, fish that aren’t caught by foreign boats are also in decline.

Something we need to recognize is that there are stocks that will continue to decline even with proper management because the environment is changing drastically.

Hanaoka: Can you see any impacts from climate change?

Koya: Yes. If the fish stock is in decline, we manage it as best we can so that people won’t say stock management itself is futile. On the other hand, we try to avert the overfishing of stocks that are increasing. There are also stocks like the walleye pollock that have declined before but are recovering when managed. It’s important to respond properly to the conditions of stocks.

Director General of the Fisheries Agency, Takashi Koya (Photo: Kazuya Hokari)

Director General of the Fisheries Agency, Takashi Koya (Photo: Kazuya Hokari)

Hanaoka: I see. Environmental factors aren’t a reason not to manage stocks, instead, they increase the importance of stock management. Moreover, it’s necessary to expand the scale of oceanic data collection and analysis, and improve the systems in order to take corrective action on environmental factors.

Koya: When it comes to stock management, it tends to be thought that it just forces the burden on fishermen to increase the number of fish, the subject is changed, and some say to us that there’s no point in there being more fish if all the working fishermen are gone. They kept telling us this but looking back now, both the fish and fishermen were gone. Ultimately, you need to persevere when the situation calls for it. If there are more fish, new fishermen will come.

Hanaoka: Its opposite never happens, does it?

Koya: At the end of the day, the goal of stock management is sustainable production, so that all the fishermen can be happy. It’s an often-misunderstood point. Our way of communication has been lacking in some respects. To avoid any mistakes, agencies always pack their presentations with so much content, like a kind of risk hedging, that readers can’t understand them. We need more training to communicate our message in a simpler way.

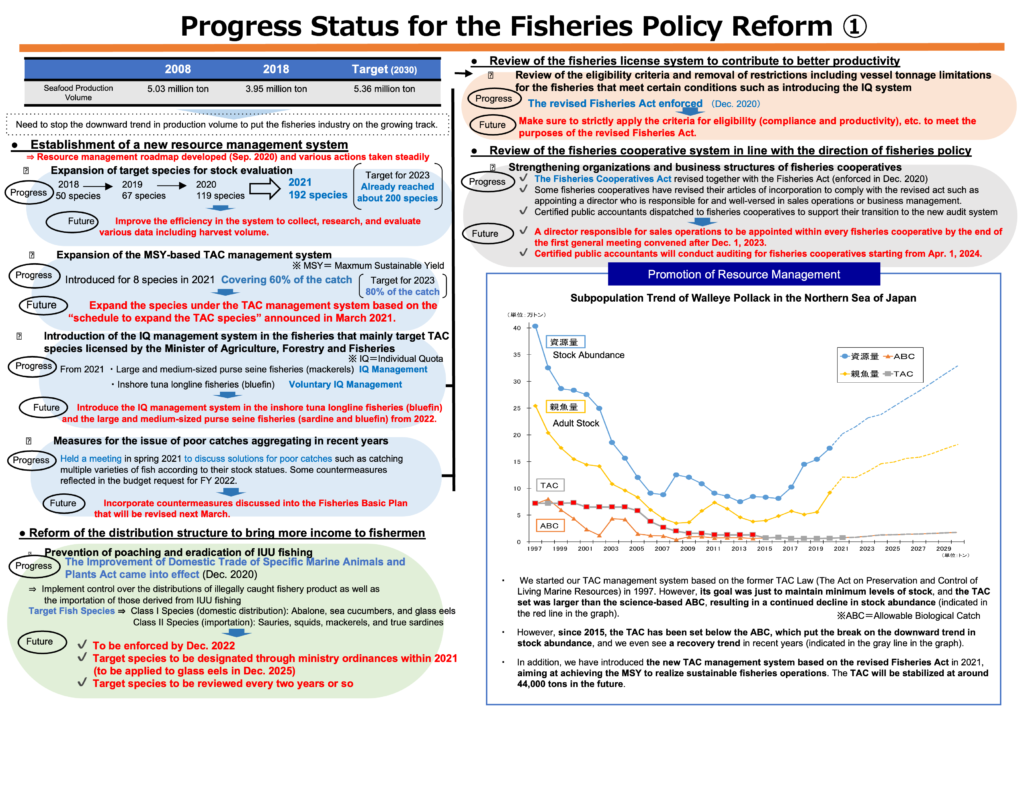

Progress on fisheries policy reforms. The Fisheries Agency is making efforts to expand the number of species for stock management.

Progress on fisheries policy reforms. The Fisheries Agency is making efforts to expand the number of species for stock management.

Hanaoka: You said at TSSS that many stakeholders distrust or are allergic to science. It would be better if fishermen realized that science is both an ally and an effective tool.

Koya: For example, when you borrow money from a bank, they draw up a repayment plan based on the numbers. When we set numerical targets in stock assessments, we get asked if such a small thing is reliable. But that’s not the right way to think about it. For example, if you want to grow profits by 10% in 10 years’ time, then it will be essential to take the current optimal approach based on the best available scientific assessments of the trends in fish stock, even as change is ongoing.

Hanaoka: Japan used to take pride in being the world leader in seafood. Somewhere along the line, we started to be treated as bad guys overfishing and overconsuming whales, tuna, eels, and so on, and I’m very concerned that this label will stick and end up weighing down Japan’s future generations who go abroad as international minded person. My hope is that Japanese people will reclaim their identity as people who know how to live in harmony with the ocean, but what do you think?

CEO of Seafood Legacy, Wakao Hanaoka (Photo: Kazuya Hokari)

CEO of Seafood Legacy, Wakao Hanaoka (Photo: Kazuya Hokari)

Koya: I feel the same way. I’m working toward a V-shaped recovery from this slump, which has not had a single recover since I joined the Fishery Agency, so I believe we’re thinking along the same lines.

Climate change is what will be important going forward. Two years ago, the Fisheries Agency opened a working group of poor catches. When looking two years later, the entire North Pacific is undergoing major changes. I think there may be no coming back from the direction it’s going. For example, take snow crabs. The snow crabs from the Sea of Japan are famous and stable, and snow crabs used to be caught on an industrial scale even off the Pacific coast of Fukushima. But since the Great East Japan earthquake, there has been a sharp decline.

Hanaoka: With almost no fishing activity, the catch should grow, but…

Koya: They’re gradually decreasing. Even in places that manage them like Alaska, the fishing was shut down this year. In other words, it’s not just fish like Pacific saury and salmon that swim on the surface; something is happening on the deep ocean floor as well. Perhaps the time has come to conduct a large-scale study and decide on a shift in policy. When it does come, there are some parts of the structure of the fisheries industry that has to change.

Hanaoka: What kind of things specifically?

Koya: In the method of stock assessment we’ve used up to now, it’s necessary to clearly delineate which waters can be managed and which waters require major reassessment, and to organize complex convoluted arguments neatly. To plan a major shift in the fishing industry in the North Pacific, where the impact of climate change is stark, I think we will need to consider what to do about things like salmon hatching and stocking, and aquaculture for the portion that we can’t make up with that method.

Hanaoka: I see. That’s a drastic change to the structure and management of the fisheries industry. I’d like Japan to demonstrate leadership in stock management in response to climate change, both in Asia and globally.

Koya: Another factor is changes in the international situation. The feed for aquaculture is mostly imported, so the price of feed is rising sharply due to the weak yen. As for how to deal with this, the TAC for Japanese sardines is actually 1 million tons, roughly speaking, yet only 600,000 tons are caught. We should use Japanese sardines to cover needs without having to import feed, but the fact is, no one wants to catch them, so they aren’t caught.

How can we get them to actually catch sardines, process them properly into feed, and provide it to the aquaculture companies at a low price? I think we need to work on creating a concrete plan that shows a growth strategy in the chain from ocean to aquaculture farm.

Hanaoka: Japan’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ) is the 6th largest in the world. Are we utilizing 100% of the potential of this vast EEZ? These waters are also ecologically rich in first place. I think that marine ecosystems are important, and not just seafood, but what approach should the Fisheries Agency take toward this area of the marine environment?

Koya: Obviously, fishery resources are founded on rich ecosystems, but taking a large-scale approach to these ecosystems is impossible for the Fisheries Agency to do alone. We have to approach the various stocks individually. One might say a more ecosystem-focused approach is important, but there’s the possibility that if we were to switch to that approach, we would end up failing to make any progress on either front. So, I think that while we continue doing our best with the individual approach to stocks, looking forward, a data collection system with a wider network that incorporates the whole ecosystem will probably be necessary.

Hanaoka: As you said, I also believe that the industry won’t survive unless we export more. While the Japanese market is shrinking, the global population is growing rapidly, so I think we should act to maximize the potential of Japan’s vast and abundant waters to ensure that Japan’s seafood industry can flourish in a sustainable way by contributing to global food security.

Koya: We had more than 100% self-sufficiency for seafood 60 or 70 years ago. It would be great if we could bring that back, but I think it’s important that we achieve this by managing the stocks in Japanese waters as best we can, unlike the old days when if you couldn’t catch anything, you’d just go further out to sea to catch.

Silver-stripe round herring migrating through Japan’s rich waters (Photo source: Ryuji Yamamoto)

Silver-stripe round herring migrating through Japan’s rich waters (Photo source: Ryuji Yamamoto)

Hanaoka: On December 1, 2022, the Act on Ensuring the Proper Domestic Distribution and Importation of Specified Aquatic Animals and Plants (hereafter: the Act) was enforced. The two largest seafood import markets, the EU and the the U.S., have already enforced measures to ban imports of seafood sourced from IUU fishing, and I think Japan may have finally taken the first step toward this as the world’s third-largest seafood import market. It has problems, such as the limited number of targeted species, but reviews every two years have been promised. In this respect, what do you think are the responsibilities of the Japanese market to the global seafood industry as a whole, and what role can the Japanese market play in the global seafood industry?

Koya: It used to feel like high-quality fish came to Japan from around the world, but these days consumption of seafood is declining, including imports. When you also consider the current weak yen, I think it will decline even more.

When the yen gets weaker, exports will automatically increase instead. For example, fish like sardines are actually very popular as feed for aquaculture, and they are being exported from Choshi and other places. With the current weak yen, from the perspective of a Japanese vendor, what would have sold for 100 JPY is selling for 140 or 150 JPY.

As this happens, it is important to consider how to build awareness that seafood from Japan is sustainable, and at the same time, to set consistent rules for imports that help achieve this. In other words, I think there will be more discussion about making imported seafood sustainable as well, using our exports as a baseline.

Maybe the destination for expensive fish from around the world, like Japan used to be, is shifting to places like China. The fish that come into Japan are mackerel and salmon from Norway. It seems like there has been a gradual shift away from high-grade fish to the kind of daily fish.

Director General of the Fisheries Agency, Takashi Koya, and CEO of Seafood Legacy, Wakao Hanaoka discuss the problems and outlook for fisheries reforms (Photo: Kazuya Hokari)

Director General of the Fisheries Agency, Takashi Koya, and CEO of Seafood Legacy, Wakao Hanaoka discuss the problems and outlook for fisheries reforms (Photo: Kazuya Hokari)

Hanaoka: Indeed, that is the trend. When we can’t demand high quality anymore, and can only import products that cut costs, there’s a major concern that this might lead to issues like human rights abuses and IUU fishing in the supply chain.

Koya: I think that’s possible, so the issues of ensuring traceability and combating IUU fishing are two sides of the same coin, and I recognize that we need to make progress there.

Hanaoka: It’s a bit unfortunate that the Act has drawn global attention, but hasn’t received much news coverage in Japan. On the other hand, I hear from intermediate distributors in Japan that many working in the field have a negative opinion of it, considering it a nuisance. But when you explain to them that it protects the companies that follow the rules from unfair competition, they get it. There are a lot of people who say that they had never thought about it that way before. This ties into what I said earlier, that it would be better if the vision for the reforms and the goals of policies came across more clearly. We all share the desire to paint a brighter future.

Koya: That’s right. That’s why I hope that everyone will support communication that agencies are not good at.

The Fisheries Agency is pursuing fisheries reforms according to a roadmap it formulated. (Photo provided by the Fisheries Agency)

The Fisheries Agency is pursuing fisheries reforms according to a roadmap it formulated. (Photo provided by the Fisheries Agency)

Hanaoka: I have high hopes for the Act and for the leadership of the Fisheries Agency on fisheries reforms, drafting a roadmap to advance new stock management policies.

We also hope to continue making a contribution to the revitalization of Japan’s seafood industry through the pursuit of sustainability.

Takashi Koya

Born in Fukuoka Prefecture in 1962. Received a Bachelor of Fisheries from the Faculty of Agriculture at the Kyushu University in 1985. Joined the Fisheries Agency in April of that year. He experienced a Vice Director General of the Fisheries Department in Ishikawa Prefecture from 2006, a Chief Negotiator of the International Affairs Division in the Fisheries Agency from 2008, a Senior Officer of the Fisheries Management Division in the Fisheries Agency from 2012, a Councilor of Resources Management Department in the Fisheries Agency from 2014, a Director of Resources and Environment Research Division in the Fisheries Agency from 2016, a Director General of Resources Management Department in the Fisheries Agency from 2017, and became a Deputy Director-General of the Fisheries Agency in 2020. He was appointed as a Director-General of the Fisheries Agency in 2021.

Wakao Hanaoka

Born in Yamanashi Prefecture in 1977. Grew up in Singapore from an early age. After graduating from the Marine Biology department at the Florida Institute of Technology, he was involved with marine conservation projects in the Maldives and Malaysia. Served as senior oceans campaigner and campaign manager, etc., for the Japanese branch of the international environmental NGO Greenpeace from 2007 before going independent. Established Seafood Legacy Co., Ltd. in July 2015, assuming the role of CEO. He works to connect diverse stakeholders in foreign and domestic business, NGOs, government, policymakers, academia, and the media and designs local solutions which are suited to Japan’s environment based on international standards.

Original Japanese text: Chiho Iuchi

Photography: Kazuya Hokari

-1024x606.png)

_-1024x606.png)

1_修正524-1024x606.png)

.2-1024x606.png)

2-1024x606.png)

-1-1024x606.png)

Part2-1024x606.png)

Part1-1024x606.png)