In ecology, there is a concept of “keystone species” that influence entire ecosystems. Researchers who applied the concept to industry in an analysis of data on the world’s top 160 seafood-related companies, drawing on the assumption that “keystone actor” companies influence the future of the world’s seafood industry, showed that just 13 companies accounted for 11% to 16% of global seafood production in 2015. In response to the researchers’ call to action, scientists and 10 of the world’s top seafood companies collaborated in 2016 to establish SeaBOS (Seafood Business for Ocean Stewardship), a global initiative to produce seafood more sustainably and improve the health of the oceans.

One of the 10 companies taking part in SeaBOS is Nippon Suisan Kaisha, Ltd. (hereafter, Nissui), one of Japan’s leading comprehensive seafood companies. Following Nissui’s decision to participate in SeaBOS immediately after its launch, Mr. Toshiya Yabuki has been involved in international collaboration as the Deputy General Manager of the company’s Sustainability Department. Part 1 of this article looks back on the sustainability-oriented initiatives that rapidly gained momentum at Nissui around 2016, as seen by Mr. Yabuki.

Toshiya Yabuki

Toshiya Yabuki was born in Japan’s Tochigi Prefecture. He graduated from the Department of Fisheries Science, Faculty of Agriculture at The University of Tokyo in 1984 and joined Nippon Suisan Kaisha, Ltd. His work since then has primarily involved aquaculture-related business in Japan and overseas. He also gained experience at overseas aquaculture sites in Chile, Indonesia, the United States, and more. He spent a total of 13 years at Chilean salmon and trout farming company and Nissui subsidiary Salmones Antártica S.A., including a term as its CEO from 2012 to 2016. He returned to Japan in 2016. Since 2019, he has worked as the Deputy General Manager of Nissui’s CSR Department (renamed to the Sustainability Department in March 2022), where he is in charge of seafood sustainability in conjunction with international networks including SeaBOS, WBA, and FAIRR.

―― At Nissui, you’ve been in charge of dealing with SeaBOS since it was launched.

That’s right. In the spring of 2016, I came back from my stay in Chile. About half a year after I became General Manager of the Aquaculture Business Promotion Department at Nissui’s headquarters, the SeaBOS matter came up. A meeting in the Maldives in November was suddenly decided. The CEOs of 10 companies nominated by SeaBOS were asked to attend, but it would be odd for the president of a Japanese seafood company to make a three-night stay in the Maldives for a little-understood meeting. I was asked to go because the meeting was in English.

―― What were your thoughts on SeaBOS when you first heard about it?

At the time, there were no specific topics set. In the Maldives, Professor Johan Rockström of the Stockholm Resilience Centre (SRC) at Stockholm University, who served as the Secretariat of SeaBOS, talked about the significance of SeaBOS and what it aimed to do. Victoria, Crown Princess of Sweden, was in attendance, as was MSC CEO Rupert Howes. This is really something, I thought.

November 11 in the Maldives. At the SeaBOS conference: Victoria, Crown Princess of Sweden (second from right); Professor Johan Rockström (third from right), then of SRC; MSC CEO Rupert Howes (far left); Toshiya Yabuki of Nissui (third from left). Photo by Jean-Baptiste Jouffray

November 11 in the Maldives. At the SeaBOS conference: Victoria, Crown Princess of Sweden (second from right); Professor Johan Rockström (third from right), then of SRC; MSC CEO Rupert Howes (far left); Toshiya Yabuki of Nissui (third from left). Photo by Jean-Baptiste Jouffray

After I reported the content of the talks to the president and upper management back at the company, in December of that year, then-president Norio Hosomi signed a formal decision to join SeaBOS. Both then and now, movements related to seafood sustainability are lagging in Japan. However, I think Nissui determined that joining was important for the company, as we would be able to discover what the issues are and gain early access to cutting-edge information by joining such a globally leading alliance.

―― Around the time SeaBOS was launching, had Nissui already started to work on sustainability?

I returned to Japan in 2016, so I can only tell you what I heard from colleagues about what was going on in Japan.

Nissui didn’t have a department devoted to CSR prior to that, so the Corporate Strategic Planning Department was in charge of CSR-related matters. That was also the time when CSR initiatives were gradually ramping up in Japan. Within the company, there was an emerging idea that we had to go beyond making contributions to society to also solidly address the social responsibilities tied to our business. The term “CSR” appeared for the first time in our medium-term plans, and the company established its CSR Department. In March of this year, the name of the department was changed from CSR Department to Sustainability Department, as the organization addresses sustainability with CSR included.

―― That’s a lot of change over a short time.

In the six years since coming back to Japan, I’ve been hearing and using the word “sustainability” a lot within the company. There are demands placed on us by our customers, and we also get information from SeaBOS. A lot of different things are being integrated, and initiatives related to sustainability keep on increasing.

―― Extending sustainability initiatives to every corner of an organization is a challenge. What sort of structure does Nissui have for doing this?

In Nissui’s head office is a Sustainability Committee, which is headed by the president and attended by all Nissui executives. Below that are subcommittees headed by executive officers, including a Marine Resource Sustainability Subcommittee and Marine Environment Subcommittee. The structure is such that subcommittees, with the heads of related departments, included, discuss specific topics and advance related initiatives. This flows down from the top throughout the whole, which helps speed up its permeation throughout the company.

―― Are there difficulties in getting people inside and outside the company to understand SeaBOS?

I think there are still a lot of people who don’t know anything about it. We’re gradually making SeaBOS known by writing about it in the company’s Sustainability Report and elsewhere. If anything, my role is to bring the latest information from overseas to Nissui.

―― Nissui has 80 to 90 group companies, including those overseas.

My sense is that we can advance sustainability more efficiently by bringing together the strengths of the Nissui Group around the world and by sharing information on matters such as best practices. However, we’re just getting started.

―― In 2016, the same year that SeaBOS was launched, Nissui conducted its first survey of fish stock. What is the background to that?

In 2016, we identified our company’s material issues, one of which is “Preserve the bountiful sea and promote the sustainable utilization of marine resources and their procurement.”

It was a problem that our company depends on fishery resources for our business yet didn’t know the status of those resources. In response to this, the Marine Resource Sustainability Subcommittee that I mentioned earlier put forth the opinion that we needed to first assess the impacts our business has on fishery resources. We surveyed our procured fishery resources in 2016, spent a year working out how to analyze the data, and published the findings in 2018.

―― How was this received within the company?

It was taken a bit negatively by salesperson who is in charge of fish species that had issues in ensuring sustainability. By contrast, the positive response outside the company was far greater than we’d imagined. At the 2018 SeaBOS conference, there was a plenary session in Karuizawa for the CEOs of member companies. When Akiyo Matono, our president at the time, announced the survey findings, there was a storm of praise. People in the industry understood what a difficult thing we’d done.

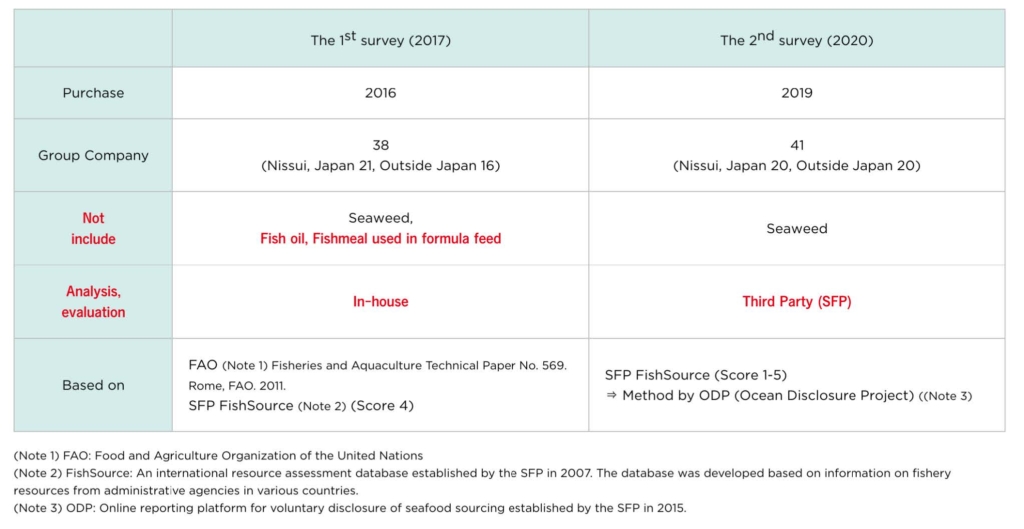

―― My impression of the second survey is that you changed the method quite a bit.

We didn’t include this in the first survey because it was difficult to confirm, but our surveys should also include fish meals and fish oil, which we handle in large volumes. So we included these in the second survey of 2019, which caused the total volume to differ by about one million tons.

Another difference is the method of data evaluation. In the first survey, we sorted data in-house while looking at published materials from FAO. But as there’s no transparency in the end without evaluation by a third party, for our second survey we asked the Sustainable Fisheries Partnership (SFP) to rate us with their FishSource score.

―― Has there been progress in understanding within the company after the two surveys?

I think there has been progresses. Things don’t end with the surveys. From the findings, it’s becoming more clear where problems lie in the fishery resources we procure, making it easier to decide how to address those. I think that’s the purpose of the surveys. The FishSource score revealed that 71% is procured from well-managed resources. Among these are some endangered species, however, and with fish meal and fish oil, the breakdown of what fish species are in there can be difficult to tell.

There are various measures for addressing fish species that face stock management issues, such as switching to MSC-certified fisheries, strengthening support for those fisheries, and implementing FIP aimed at MSC acquisition. From here on out, we have to do these things while discussing a lot of things with relevant departments in the company. It’s not an easy task.

―― Does the FishSource score incorporate items related to human rights?

No, it only includes compliance items for fisheries management. Human rights are not distinctly included. Because of that, we have to check on IUU fishing and forced labor through other means.

―― Measures against IUU fishing are included among SeaBOS’ task forces, aren’t they?

That’s right. Companies are struggling with this. The goal last year was no IUU fishing or forced labor in companies’ operations, which all 10 companies achieved, However, the problem is the supply chain. Stepwise progress is being made toward the goal of enabling checks that extend to Tier 1 (primary suppliers) and Tier 2 (secondary suppliers).

―― What has been positive about taking part in SeaBOS?

In addition to the 10 major seafood producers in SeaBOS, scientists from the SRC and elsewhere also participate. We’re able to refer to advice from scientists’ points of view, not only companies’ reasoning.

Participants attended a lecture by Stockholm Resilience Centre (SRC) scientists at the SeaBOS Maldives conference in November 2016. Photo by Jean-Baptiste Jouffray

Participants attended a lecture by Stockholm Resilience Centre (SRC) scientists at the SeaBOS Maldives conference in November 2016. Photo by Jean-Baptiste Jouffray

There are some topics that we’ve never heard about in Japan and that are tough to follow in English. But when we ask SRC or other scientists to tell us a little more about it, they very generously provide information.

If we want information on aquaculture, for example, among the 10 companies in SeaBOS we can inquire to aquaculture companies like Mowi or Cermaq, which kindly provided information. The advantage of a worldwide network is big.

―― So you have good communication with the member companies.

Yes. Three Japanese companies—Maruha Nichiro, Kyokuyo, and our company—are in SeaBOS. I don’t think there were many opportunities in the past for Japan’s three major seafood companies to meet and share information or exchange opinions. Since joining SeaBOS, however, there have been more opportunities to informally talk about SeaBOS-related topics with them.

―― So cooperation among domestic companies has become stronger.

In terms of relations with government agencies, instead of separately going the Fisheries Agency, for example, the three companies can visit together to offer their thoughts, which has a greater impact on the Agency. I think this is one way that SeaBOS is effective.

―― Are there issues other than IUU fishing that SeaBOS is focusing on?

It’s working to reduce the use of antibiotics at aquaculture farms. In particular, it’s working to set a goal of using Critically Important Antimicrobials (CIA) specified by WHO as little as possible, as these overlap with antibiotics used in human medical care. In Japan’s case, some antibiotics approved by the government for aquaculture farms are classified by WHO as CIA, but no effective vaccines or drugs exist to replace these, which makes it a very difficult issue.

As this cannot continue, the three Japanese companies in SeaBOS are exchanging information with pharmaceutical companies and administrative authorities to gain understanding, and are working to create a platform for advancing the development of new vaccines. (Continued in Part 2)

Part 2 will focus on issues facing the seafood industry as seen by Toshiya Yabuki, who has years of experience working at Nissui’s overseas aquaculture farms and who currently works to promote seafood sustainability while dealing with SeaBOS and other international networks.

>> Read Part 2

Original Japanese text by: Chiho Iuchi

-1024x606.png)

_-1024x606.png)

1_修正524-1024x606.png)

.2-1024x606.png)

2-1024x606.png)

-1-1024x606.png)

Part2-1024x606.png)

Part1-1024x606.png)