Taking an interest in the relationship between the oceans and humans while aspiring to become a marine biologist, Erin Taylor has been working at FishWise, an organization that works with seafood companies to achieve sustainability. In Part I, we spoke with her about the background and difficulties involved in human rights due diligence, which seeks to protect human rights and workers’ rights in the seafood supply chain. (Read Part I)

In a look at more specific activities, Part II introduces the Roadmap for Improving Seafood Ethics (RISE), a guide created for companies undertaking seafood-related human rights due diligence, and also asks about expectations toward Japanese companies.

――Today you’re taking part in our interview from Ecuador. What are you doing in that country?

I’m staying at Manta, a fishing port in Ecuador and one of the world’s leading tuna processing sites. We’re working with FAO’s Blue Ports Initiative to hold a workshop here with participation by Latin American governments, companies, industry associations, civil society groups, technology providers, and other parties.

The workshop is trying to shed light on the role of traceability at fishing ports, related to the Comprehensive Traceability Principles developed through the Seafood Alliance for Legality and Traceability (SALT). Fishing ports are critical seafood distribution hubs and have a key position in supply chains. Using traceability effectively leads to benefits in economic, environmental, and social aspects for stakeholders in the supply chain. The aim of the workshop is to focus on port processes and how traceability can enhance those processes to maximize comprehensive benefits; this work is bringing together stakeholders who may not normally be working with each other, but whose collaboration can lead to greater benefits.

――SALT is really taking on traceability around the world.

SALT itself is a six-year global project funded by the US Agency for International Development, but we’ve been working on local projects with a number of producer countries, leveraging the network that FishWise has built up. In Tanzania, Vietnam, and Latin America in particular, we worked to introduce the Traceability Principles together with local partners to help guide stakeholders in these countries in building their own traceability programs. SALT is a global community that connects traceability experts and practitioners. Through the project, we’ve formed a network that connects over 2,000 professionals from over 80 countries.

──Are there differences among countries or cultural zones?

Some unique attributes always come up as you dig deeper into individual cases, but over the course of SALT’s activities, there are way more similarities than differences in the challenges people face. Inability to properly assess data on workers, opaque working conditions, lack of standards and systems across whole regions, unclear benefits for fishers…these are common issues that go beyond cultures and borders.

We collected the challenges to introducing traceability across regions and put together the Traceability Principles as a guide for addressing these challenges. There are six principles that cover topics including verifying data, being inclusive when building data systems, and scaling actions once started. Our goal was to create a guide that is broad enough to apply to a wide range of cases, but also specific and practical enough to steer companies and administrative authorities toward action. We formed a worldwide committee of 35 experts involved with traceability in some form to develop the Traceability Principles. In the Principles, we emphasize a holistic approach, which means that traceability programs can and should strive for environmental, social, and economic outcomes.

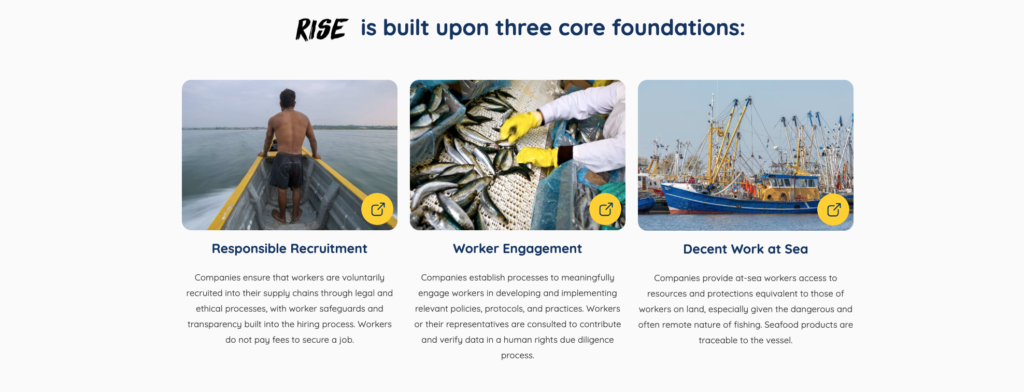

For the social responsibility of companies, human rights and labor issues are urgent issues. As a guide for supporting initiatives, FishWise created the Roadmap for Improving Seafood Ethics (RISE). This can be used for self-assessing a company’s current situation, identifying areas for improvement, and formulating strategies for tackling human rights issues.

There are also practical tools available on RISE, including free e-learning courses, worksheets that can be used for internal review of procurement policies, and case studies accessible online. For those who don’t know where to start, RISE guides users to content matched to their business via a self-diagnosis based on answers to a number of questions.

The three foundations at the core of RISE: Responsible recruitment, worker engagement, and decent work at sea.

The three foundations at the core of RISE: Responsible recruitment, worker engagement, and decent work at sea.

──When the issues are this big, it can certainly be tough to know where to start. Are there some opportunities that let anyone involved in the seafood industry make a small start?

In the seafood sector, activities related to social responsibility run the gamut. One of the easiest things for a company to do is to start dialogue with suppliers. A lot of companies view human rights issues as some far-off matter that has nothing to do with them, as something they don’t believe exists in their supply chains because they trust their suppliers, or as something they don’t believe they can do anything about.

But asking questions is something that anyone, in any position, can do. I often hear, “We don’t need to ask, because we’ve known and trusted our suppliers for a long time.” But if that’s the case, and trust exists, then there’s no reason to hold back from asking questions. We’re not suggesting approaching this in an accusatory way; rather, you are just wanting to better understand practices. Even if you approach your supplier and they don’t know an answer, that’s not a bad thing in and of itself. You can search for answers and learn together.

There are tools and resources to use in a dialogue like this. You could share the self-assessment tools we offer on RISE, for example. In any case, finding out what is or isn’t happening is the first step.

For initiatives in this area, using a punitive approach first would not be constructive. The goal is not to attack shortcomings. Even if you find that there’s a problem with a supplier, simply cutting off business with them won’t fix anything. We should take the time to aim for improvement through joint work. Buyers often have the power to change sellers’ practices. We want buyers to exercise that power.

――Are there any particular expectations toward Japan’s seafood industry?

In a country with a giant market like Japan, there is great significance in seafood businesses taking a stand. The first step is for companies involved in seafood to realize and acknowledge that they shoulder responsibilities and roles to play. They can start by making declarations of their efforts, then move one step at a time toward practical actions. Even if results aren’t seen right away, it’s important that the process of improvement move forward.

From there, we’d definitely like to see companies act not only on their own, but to also actively participate in pre-competitive industry initiatives. The issues have to be tackled through a collaborative framework; they can’t be resolved by one company or one supply chain alone. Collaboration exerts power.

――Taking that first step often seems difficult to do. What kind of triggers and motivations do you think would make companies involved in seafood make the decision to tackle human rights due diligence?

In behavioral psychology, a field I’ve increasingly been looking into to apply to our own work, the Fogg Behavioral Model is an interesting framework to consider. This model says that three things are needed for people to take action: motivation, ability, and prompts. Of these, the motivation that people have inside themselves isn’t easily swayed. So, it’s more fruitful to think about working on the other two things so that people who already have motivation can take action.

In my work with a lot of companies, I’ve seen many examples where exposures to some sort of new information, like conversations with suppliers or peers, or news and articles, become a prompt for action. However, as I noted, even when prompts exist, a lot of people think that they lack the ability to change the situation.

But there is always something that people can do, whatever their positions may be. And small things add up to become big change. Buyers can build evaluation of human and labor rights practices into their formal processes for selecting suppliers (RISE can help here). Managers can listen to seminars, look into labor-related information, and explore ways to engage with workers in more meaningful forms. People in marketing or public relations work can ask internal teams about their human rights initiatives, and communicate about these activities publicly.

Legislation also has an important role to play. As I noted in the difference between the Boston and Barcelona Seafood Expos, existing or upcoming regulation accelerates companies’ actions. When there are only voluntary actions, businesses can get dragged down in the long run by price competition. Having regulations encourages a more level playing field.

Regulations can also become a strength for a country’s industry. Countries that have clear legal regulations and enforcement concerning human rights and labor issues have an advantage in exporting to countries that impose strict conditions. Countries that rely on self-regulation can be seen by counterparts as high-risk trading partners.

Personally, though, I don’t think such a complicated issue can be reduced to black and white. There’s no model that fits all, and no matter how good a solution is, 100% adoption and adherence is difficult. But the lack of a perfect solution is no excuse for doing nothing. It’s about acting with urgency, then always asking ourselves what we can do, and continuing to execute on that. By doing so, we can help push progress toward a world in which violations of human rights and worker rights have been eliminated from the seafood industry and in which everyone can engage in decent work.

Erin Taylor

Senior Project Director, Business Engagement and SALT (Seafood Alliance for Legality and Traceability), FishWise. Active across divisions at FishWise, Erin Taylor builds and manages holistic sustainability programs with corporate partners, government bodies, and external collaborators. She leads partnerships aimed at achieving sustainability goals and improving supply chains, with the involvement of industry associations and companies in retail, distribution, hospitality, and other sectors. In recent years, she has addressed social responsibility in business, supporting companies in taking up human rights and the rights of workers as issues. She recently joined FishWise’s SALT team and now leads activities with governments, industry, and NGOs in Latin America and the Caribbean and globally. Prior to joining FishWise, she was a wild fisheries specialist at the New England Aquarium, advising large companies on marine products-related issues including traceability, policy, certification, fisheries improvement, and environmental risks. She holds a BA in Environmental Analysis & Policy from Boston University.

Original Japanese text by: Chiho Iuchi

-1024x606.png)

_-1024x606.png)

1_修正524-1024x606.png)

.2-1024x606.png)

2-1024x606.png)

-1-1024x606.png)

Part2-1024x606.png)

Part1-1024x606.png)