Drawing on his extensive experience in the financial sector, Mr. Takejiro Sueyoshi serves as a Special Advisor to the United Nations Environment Programme Finance Initiative (UNEP FI) and has worked tirelessly to develop mechanisms aimed at addressing environmental issues. We had the opportunity to speak to him about his thoughts on what is necessary for sustainable seafood initiatives from the perspective of someone at the forefront of the movement to introduce a global environmental perspective into Japan’s society and economy, including his launch of the Japan Climate Initiative (JCI) in 2018.

Takejiro Sueyoshi

A Special Advisor to UNEP FI, Sueyoshi graduated from the Faculty of Economics at the University of Tokyo in 1967 and joined Mitsubishi UFJ Bank (now MUFG Bank). He became Branch Manager and Director of the New York branch in 1994 and was appointed as Chairman of the Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi Trust Co. (NY) in 1996. In 1998, he was appointed Vice President of Nikko Asset Management, and he was named as a member of the UNEP Finance Initiative (FI) Global Steering Committee during his tenure. Since 2002, he has been actively engaged in environmental issues and was instrumental in convening the UNEP FI Tokyo Global Roundtable and the issuance of the Tokyo Declaration. He was appointed as a Special Advisor to UNEP FI in 2003.In 2011, he was also appointed as a Renewable Energy Institute, Vice-Chair of Executive Board.In 2018, he launched the Japan Climate Initiative (JCI), where he serves as Representative. He was also appointed Chairperson of WWF Japan in the same year.

――As someone who has long been engaged in the development of global socioeconomic mechanisms to address environmental issues, could you share your thoughts on the current situation of sustainable seafood and its prospects in the near future?

Until now, most of the focus has been on “climate” (C) as a global environmental issue, but attention is finally beginning to turn towards “nature” (N), which also encompasses living organisms. We need to keep a close eye on both these aspects as we move forward.

A large part of this “nature” is the ocean, and there are actually several aspects to this. Firstly, the ocean absorbs around one-third of the CO2 on earth, which in turn inhibits a spike in the CO2 concentration in the atmosphere. However, the more CO2 the ocean absorbs, the more acidic seawater becomes, crustaceans such as shrimp and crabs are unable to solidify calcium and build shells to protect themselves.

There is also the problem of rising ocean temperatures. Even a 0.1°C rise in water temperature can have a major impact on biological environments. Common effects include coral bleaching and changes to the locations where fish is caught. For example, the Pacific saury is no longer caught in Hokkaido, and the Spanish mackerel from the Sea of Japan is now caught closer to the Pacific Ocean, so I think we need to approach seafood-related issues from the perspective of how these issues affect the ocean as a habitat for fish.

It is also important for us to keep in mind what the word “sustainability” means. In 1987, the World Commission on Environment and Development chaired by Gro Harlem Brundtland, Norway’s first female Prime Minister, issued a report entitled “Our Common Future,”* in which the phrase “sustainable development” was defined as “meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.”** In other words, “sustainability” is based on the concept of fairness across different generations.

Today, the term “sustainability” is bandied about everywhere, but most of the discussion is simply about how the timeline of our current generation can be extended. Sustainability, as it was originally conceived, requires us to respect the human rights and the right to live that should be accorded to our children, grandchildren, and future generations. For instance, if the younger generation in Japan is no longer able to take over our fisheries, we would have compromised the human rights of future generations. Of course, we also need to consider the needs of our current generation, but it is imperative for us to look further into the future.

The 50th-anniversary conference of the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment (Stockholm, 1972), which led to the establishment of UNEP (United Nations Environment Programme)*, was held in Stockholm this spring.

The first environmental issue taken up by the United Nations at the 1972 conference was that of marine pollution, in addition to acid rain damage in Northern Europe. Environmental pollution has been a problem in Japan since the 1970s, and both its causes and damage are entirely visible. The causal relationships surrounding marine pollution, however, are more difficult to grasp as its causes and damage straddle national borders.

Today’s environmental issues cannot be resolved without a coordinated international response. The ocean, in particular, is emblematic of what is termed “global commons,” a borderless area that is shared by everyone on earth. Now that it has become unsustainable for us to think that anyone is free to take whatever is available since it is common property, our challenge is how to best protect this common property.

――What role will the financial sector play as the world makes this transition?

The “Rio Summit” (United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, or UNCED), also known as the “1st Earth Summit,” was held in 1992. At that time, those in the private sector who were interested in environmental issues were primarily the industrial sector. They recognized that their business activities had a direct impact on the environment.

On the other hand, there was a sense that the financial industry only handles money and carries out its work in offices across cities without causing any pollution. Yet, if we think about it, our society and our economy cannot exist without the financial sector. Why was this sector so apathetic to global issues?

In the run up to the Rio Summit, the predecessor of UNEP FI was launched with the participation of more than 30 banks, mainly from Europe. I was still working for a bank in New York at the time, and there was no interest at all from Japanese banks then.

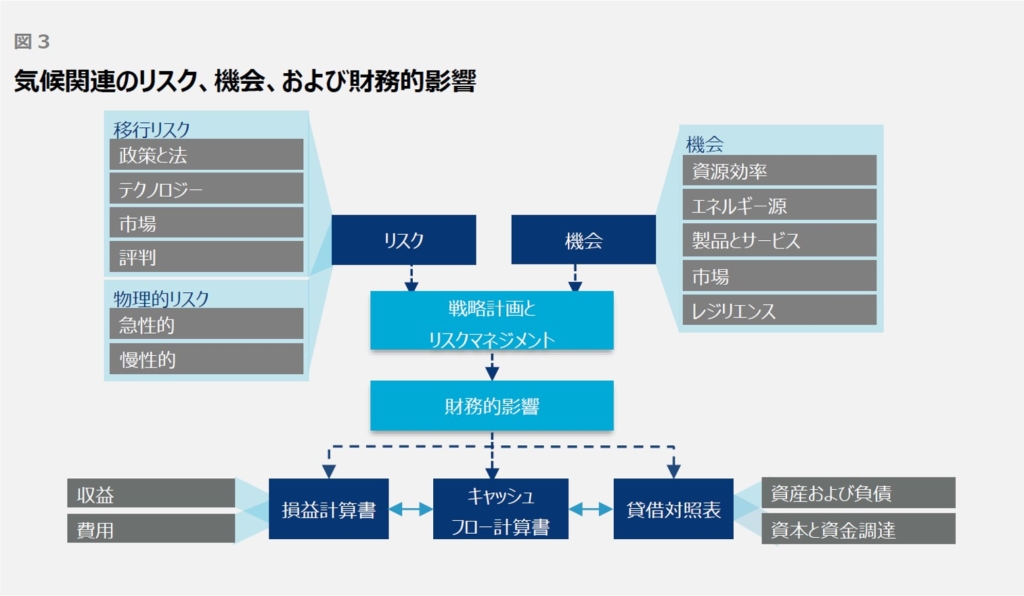

In order for the financial sector to play a more concrete role, the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) began its work in 2015. Its goal was to create a system in which companies are required to project future scenarios and forecast their strategies in terms of both risks and opportunities in relation to climate change, and disclose these in monetary terms. When financial institutions screen borrowers based on this information, the flow of capital changes.

Moves to make such a system mandatory have started to be made in many countries. The United Nations and other organizations have also begun discussions to address not only “climate” (C) but also “nature” (N). Companies will no longer be able to survive without disclosing information related to climate change and biodiversity. Seafood is also a part of this larger movement.

TCFD requires companies to disclose in their financial information the risks and opportunities for their business related to climate change, how such risks and opportunities would be approached, and their strategies to avoid the risks and take advantage of the opportunities. Source: “Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD): Implementing the Recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures” (Japanese translation by the TCFD Consortium and the Sustainability Forum Japan under the supervision of Masaaki Nagamura and the Steering Committee of the TCFD Consortium, October 2021)

TCFD requires companies to disclose in their financial information the risks and opportunities for their business related to climate change, how such risks and opportunities would be approached, and their strategies to avoid the risks and take advantage of the opportunities. Source: “Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD): Implementing the Recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures” (Japanese translation by the TCFD Consortium and the Sustainability Forum Japan under the supervision of Masaaki Nagamura and the Steering Committee of the TCFD Consortium, October 2021)

Whenever there is money to be made, people will always rush to make the money. When I was in New York, Tsukiji tuna was highly sought after because of the Japanese food boom, so there were companies shipping tuna caught in Boston to Tsukiji before shipping it back to New York, where it was marketed as “Tsukiji tuna” and sold at high prices. The same thing is happening in Japan. It is natural for people to want to sell the fish they caught at the highest price possible.

What this means is that, ultimately, it all comes down to the choice of consumers. This issue does not revolve around a few industries or the words of experts but involves our everyday dietary habits. What choices will consumers around the world make in relation to seafood? That is the most critical factor.

In a salmon farm in Norway owned by one of the general merchants and traders, hundreds of thousands of salmons in the ponds are individually tagged with IT and managed in a manner that minimizes stress. By ensuring the well-being of the fish and reducing their stress, the salmons grow well and taste better. Consumers found value in this venture, and it has become a successful business. This is the kind of economic cycle we need to create.

The business is being created in which aquaculture methods that conserve marine resources and respect the wellbeing of sea creatures produce delicious salmon.(Images are stock photos)

The business is being created in which aquaculture methods that conserve marine resources and respect the wellbeing of sea creatures produce delicious salmon.(Images are stock photos)

In Part 2 of this article, we will look at current business trends where companies have finally started to acknowledge and respond to the substantial threat of climate change, as well as the “new game” of GX (green transformation), where competition is beginning to emerge. We will also speak to Mr. Sueyoshi about how Japan has been left behind in this global transition, the reasons and background for this, new initiatives that go beyond the existing framework of governments and economic organizations, as well as what is expected of the management teams of companies as we move forward.

Original Japanese text by Keiko Ihara

-1024x606.png)

_-1024x606.png)

1_修正524-1024x606.png)

.2-1024x606.png)

2-1024x606.png)

-1-1024x606.png)

Part2-1024x606.png)

Part1-1024x606.png)