Part2-1024x606.png)

The amendment to the Fisheries Act, which is said to be the first overhaul of the law in 70 years, was passed in December 2018 and went into effect in December 2020.

The amended Fisheries Act states “sustainability” as its objective for the first time and stipulates an expansion of the target species of stock assessments from 50 species to around 200 species over coming five-year period. It also introduced the Maximum Sustainable Yield (MSY) as an effective standard for stock management, promoted the management of Total Allowable Catch (TAC) based on MSY, and introduced the concept of an Individual Quota (IQ). The administrative responsibilities of the national and prefectural governments have also been established.

We spoke to Dr. Toshio Katsukawa, who has been a powerful advocate for the necessity of stock management, about his thoughts on the amended Fisheries Act and the current circumstances surrounding Japan’s fisheries.

—What are your thoughts on the amended Fisheries Act, which is said to be the first overhaul of the law in 70 years?

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, also known as the Law of the Sea Convention, grants coastal states a 200-nautical mile exclusive economic zone while imposing on them the obligation to manage fishery resources based on MSY. Until now, Japan has not fulfilled its stock management obligations even as it claims control over its exclusive economic zone, but the amended law allows it to regulate the catch of fisheries, which is an obligation of coastal states.

I have previously criticized the failure of Japan’s fisheries policy to fulfill its management obligations, but now that the law has been amended by political leadership, the government’s attitude has clearly changed. In this regard, I believe that this legal amendment is a significant step. The fact that the law was amended in a top-down, politically driven manner demonstrates the importance of having our politics show the right path forward.

—Many Japanese people find it hard to understand why the government has finally decided to act on an issue that has been in limbo for the last 70 years.

That is unclear part.

The amended Fisheries Act has introduced the concept of an Individual Quota (IQ).

The amended Fisheries Act has introduced the concept of an Individual Quota (IQ).

In 2014, a special feature on fishery resources titled “How Japanese people catch all the fish in the ocean,” to which I had also contributed, was published in Wedge, a magazine that was available in the green cars of the bullet train. This special feature caught the attention of Fumiaki Kobayashi, a Diet member who was on his way back to his hometown of Hiroshima. He then asked his brother, who had taken over his family’s fishing net manufacturing business, if the content of the publication was true.

This made him realize that our seafood industry was in a state of crisis, and he decided to take action to address it by gathering people who were familiar with the situation, especially younger Diet members , to create a movement aimed at amending the Fisheries Act.

Elected politicians decide the direction of the country under Japan’s democratic system, and in this case, it can be said that this process worked. However, because this change in direction had not been taken after consulting with the general public and the industry and securing their agreement, the major challenge we now have to take on is to transform the attitudes of people on the ground.

—It has been a little more than half a year since the law went into effect, but how much of a difference has it actually made?

Of course, just because the law has been amended does not mean that the world will change 180 degrees. There are still many problems that remain, including those that we have been avoiding. Because we have finally stopped procrastinating and started looking for solutions to our problems, things may be more confusing than before in the short term. However, I support this process because it is critical to the survival of Japan’s seafood industry.

—What kind of activities has the Association for Sustainable Seafood for the Future engaged in to raise public awareness of the issues surrounding our fishery resources?

This organization was launched in 2013 in view of the impending amendment to the Fisheries Act, and there was a time when we were also rather active on social media. Our starting point was to make sure that any amendment made to the Fisheries Act would be effective. At the time, the Fisheries Agency was opposed to the amendment and claimed that they would not impose any fishing regulations as there was no problem, and we argued in response that the industry would have no future if the status quo persisted.

The Seafood Symposium held at Waseda University in May 2016 by the Association for Sustainable Seafood for the Future

—What kind of approach do you have in mind as we move forward?

Following the recent amendment to the law, it is clear even to outsiders that the Fisheries Agency has been making an effort to move forward in compliance with the law. If we adopt a confrontational stance and point out problems in an aggressive tone as we had in the past, we may end up sabotaging our goals.

Also, while we needed to lobby the legislative branch and the government bureaucracy in the past when it was necessary for the law to be amended, we now need to focus on transforming production and consumption sites in order to build a system that can support fish consumption moving forward. Although it has not been easy to do this during the COVID-19 pandemic, we intend to shift our focus to activities closer to people on the ground.

Japanese consumers are not really interested in sustainability and dislike cancel culture,* so the approach of eliminating seafood products without eco-label certifications from the market, as in the U.S. and Europe, is not likely to win over anyone. I feel that unless we can commit to tackling the problem of sustainability while ensuring people still have access to delicious and enjoyable food, we may have a hard time expanding the market and keeping the movement alive.

—In other words, your approach is not one that is focused on the social issues.

Rather than advocating for abstract ideas such as ethical consumption, I believe the shortcut is simply to let consumers know what is happening on the ground at fisheries.

In the current situation where consumers have become alienated from producers, it is inevitable that consumers only take their own interests into account and focus on how they can buy high-quality products at low prices. However, if consumers get to learn more about the production sites and witness how much effort and pride producers put into their work, they will become more inclined to support the producers. Once they get to know the production sites, they will be able to see the depletion of resources and the problems in distribution.

Therefore, the first step is to bring producers and consumers together. We are currently working on an initiative aimed at creating points of contact between producers and consumers. It is enjoyable to know who produces the food you eat and how they do so. By creating more of such opportunities, we can raise awareness among consumers and motivate them to take action so that they can continue to enjoy seafood products.

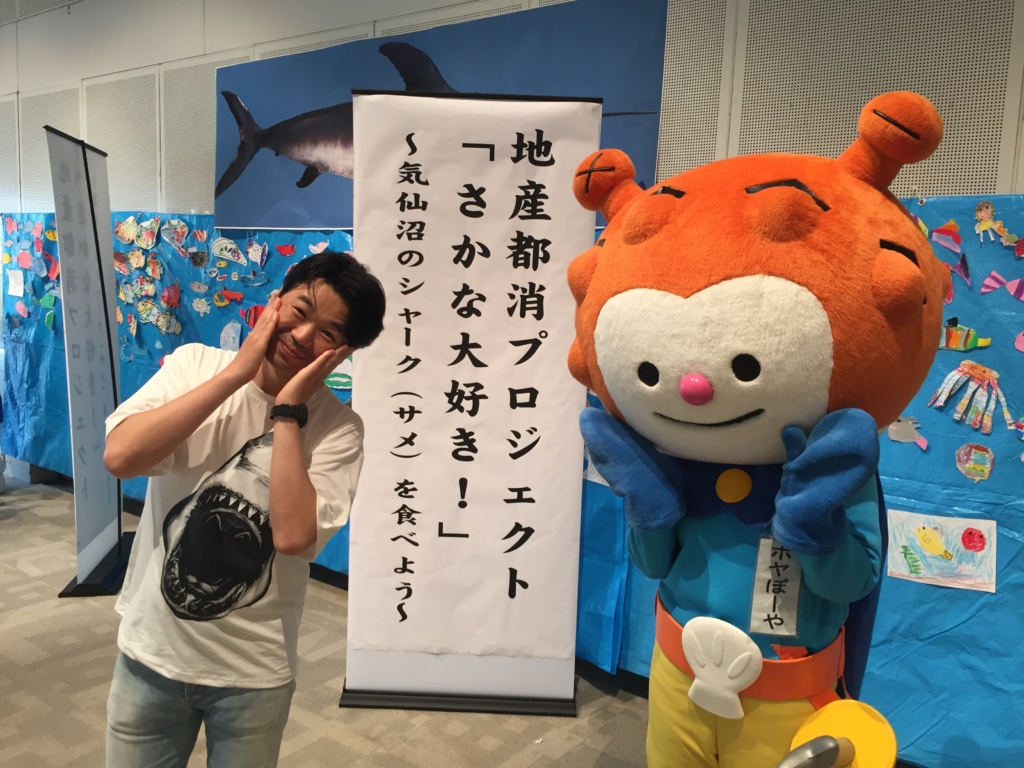

The “I Love Fish!” Project allows children to learn more about what goes on in the fisheries industry

The “I Love Fish!” Project allows children to learn more about what goes on in the fisheries industry

We recently launched “I Love Fish!”, an educational project conducted in collaboration with local governments that aims to connect consumers and producers. Children in Tokyo get to listen to professional fishermen, come into contact with real fish and fishing equipment, and learn about the fisheries industry, before they are served fish that has been shipped directly from production sites. Through this hands-on experience of hearing, seeing, touching, and eating, children will become more familiar with our fisheries industry.

We believe that increasing the number of fans of Japan’s seafood and fishermen will drive consumers to become more engaged and support our fisheries industry moving forward. From the perspective of producers, having more young fans will give them a sense of fulfillment and raise awareness of the issues surrounding the sustainability of resources and fisheries that need to be addressed for children to continue consuming fish.

As we move into the future, I hope to play a part in fostering a sustainable seafood industry through close collaboration between producers and consumers while growing the number of people who are fans of Japan’s seafood industry.

Toshio Katsukawa

Born in Tokyo in 1972, Toshio Katsukawa graduated from the Department of Fisheries, Faculty of Agriculture, The University of Tokyo, and he has a phD in Agriculture. After serving as Assistant Professor at the Atmosphere and Ocean Research Institute, The University of Tokyo, and Associate Professor at the Faculty of Bioresources, Mie University, he was appointed as Associate Professor at the Office of Liaison and Cooperative Research, Tokyo University of Marine Science and Technology, in April 2015. He has continued to engage in efforts to make fisheries a growing industry while traveling around Japan and abroad. Katsukawa is a recipient of the Encouragement Award and the Dissertation Award from the Japanese Society of Fisheries Science (JSFS). His major publications include Japan’s Fisheries Industry Problem (NTT Publishing) and The Day We Will No Longer Be Able to Eat Fish (Shogakukan Shinsho). He is a board member of the Association for Sustainable Seafood for the Future.

-1024x606.png)

_-1024x606.png)

1_修正524-1024x606.png)

.2-1024x606.png)

2-1024x606.png)

-1-1024x606.png)

Part2-1024x606.png)

Part1-1024x606.png)