Fixed-net fishing is a traditional Japanese fishing method. Unlike other fishing methods that involve going to the coast or offshore to search for fish, this method lures migrating fish by placing the net in a fixed location in the sea. It’s also known as “machi no ryō (wait-and-see fishing)” and has taken root in local coastal areas.

However, it’s not easy to catch only specific fish species with the wait-and-see format, making it a prerequisite to go for many fishes. This gave rise to opinions that it’s difficult to manage resources with fixed-net fishing or it catches almost-depleted fish resources.

Amid all this, one person asserts the potential of fixed-net fishing to become a sustainable method, talking about its sustainability and future. This is Hiroshi Izumisawa from Izumisawa-Suisan Co., Ltd.

Mr. Izumisawa manages nine fishing grounds across Japan, mainly in Kamaishi City, Iwate Prefecture. He’s also engaged in fixed-net fishing in other areas, including Miyagi, Shizuoka, and Hokkaido. A leading figure in the fixed-net fishing industry, he even attended the Cabinet Office’s Council for the Promotion of Regulatory Reform concerning the Fisheries Law, which was revised for the first time in 70 years.

Let’s hear more from Mr. Izumisawa about the future of fixed-net fisheries.

–Please tell us about the current debate about fixed-net fisheries.

One point that has been raised is, “Can fixed-net fisheries control their catch?”

Well, there’s the Total Allowable Catch (TAC) as a rule of protecting and managing fishery resources. There are currently seven fish species being caught in large quantities in Japan that require special resource management. In the next five years, 80% of the fish catch, or about 20 fish species, will be subject to regulations.

When this happens, many would likely ask whether fixed-net fishing can be selective, for example, catching or not catching specific fishes. Here, I would like to explain that in the first place, fixed-net fishing has always been able to selectively catch fish species.

Fixed nets can catch different fish depending on the region and season. That’s why the fishing gear we already have is also conscious of fish species selection.

There are old-fashioned types for getting large quantities of heavily caught fishes* like mackerel and sardines, as well as nets for catching migratory fish like yellowtail in areas with fast tides. There are even models specialized only for salmon in Hokkaido. These choices allow us to be conscious of what type of fixed net to use for catching which species of fish.

*Refers to fish caught in large quantities at one time, such as sardines, mackerels, scads, etc. Fish in this category have extremely variable resource/catch quantities.

In the first place, the fish are basically still alive until the fixed net is raised and the landing is done. If the net is left unattended, some fish will escape, making selective fishing possible.

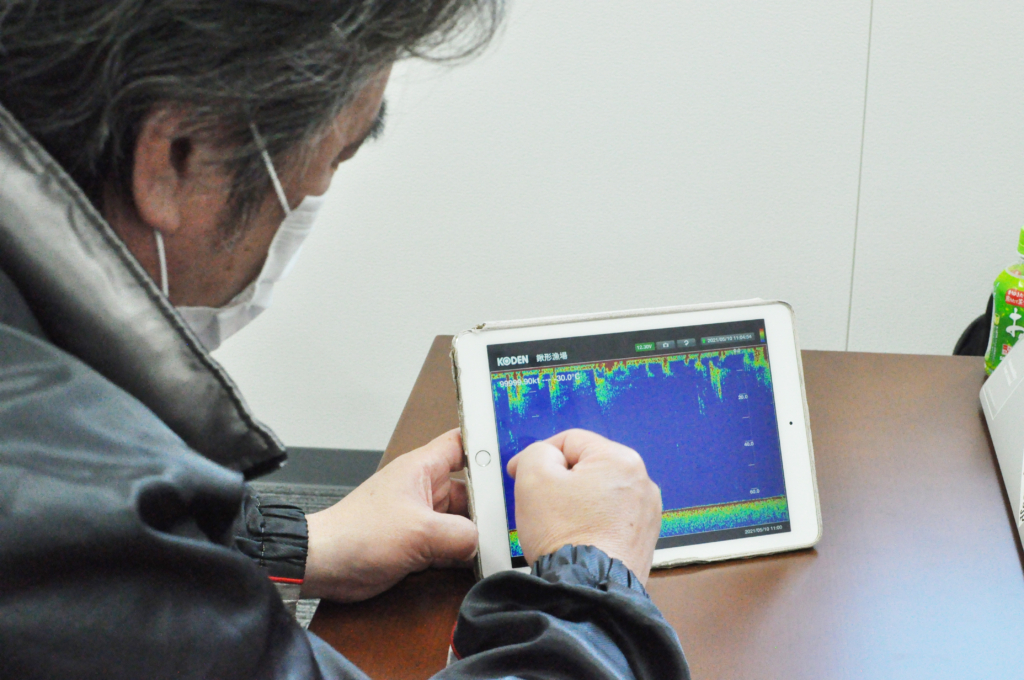

We implemented IT in some of our fishing gear and recently found out that different fish species come into the fixed nets depending on the time of day. This means it’s theoretically possible to select which schools of fish to catch by controlling the opening and closing of the fixed net according to the time.

–So, if we can improve the fishing gear and digitalize the fixed-net fishing method, we can reliably and selectively catch fish like other fisheries.

That’s right. Different fishing styles, such as purse seine and trawl, have different methods of catch control. Fixed-net fishing must also have its own unique way of managing resources.

–There are so many possibilities in “wait-and-see” fishing.

On the other hand, the purse seine and trawl fishing methods use operational fishing gear to catch fish by actively moving to the school’s location. In other words, even with fewer fish, they can still find schools and catch them. However, there’s also the possibility of unintentional bycatch, making it difficult to completely control the catch.

Fixed-net fishing uses fixed fishing gear, so if the fish don’t swim to them, we can’t catch no matter how much time passes. More fish means more opportunities to catch, while less fish means fewer opportunities, meaning it greatly depends on the resource situation. It’s like a fixed-point observation station for grasping the number of resources.

I believe that if we properly convey our side of the story, people won’t be saying things like,

people won’t say that you can’t manage fish stocks as long as you just wait for the fish to come.

–We feel that fixed-net fishing using fixed gear has a strong aspect of being a local occupation.

If you go back in history, there were settlements all over Japan that existed because of fixed nets. The fisheries were rooted in the local community, serving as a source of employment for fishermen, with the sales of the fish generating income for the merchants.

It was such a core foundation of people’s lives that if the fixed net disappeared, the entire village would go out along with it. However, places like these may gradually disappear with the changing times.

–What do you think about the survival of such fixed nets?

Whether or not the fixed-net fishing method will survive in the future will make a difference from region to region. The government’s resource allocation and which ports to sustain largely depend on the market. Nowadays, companies and organizations are being protected, which in turn protects the individuals belonging to them, and it’s easier for the government to manage them this way.

However, what we as a country should protect is each individual citizen. So really, there should be other ways of thinking aside from protecting only companies, groups, and villages. We need to decide where to build infrastructure and consolidate functions. That way, we can promote collaboration and consider a wider area for fishing.

–Izumisawa Suisan also operates fisheries outside of Iwate Prefecture. Is that based on the same idea?

Yes. Fishing is affected by weather, so there are large fluctuations in catch from year to year. The catch completely differs from region to region. Even on the same island, the fish you’ll get is completely different depending on which side you’re on. Unless we can equalize this within our own pockets, coastal fishing cannot be sustained as a business.

This is why we operate multiple fixed nets in far-flung locations. It’s a risk hedge, if we can’t catch well here, we will catch some in other areas.In truth, every region goes through its own “good times and bad times.” In Japan’s fishing industry, you can only catch fish in your own ground (=the fishing grounds you manage). In other words, if the fishing ground in the area is no good for a decade, the fishing industry there will go out along with it.

–What do you think is the biggest challenge for the Japanese fishing industry?

For me, it’s the inability to dispel the micro nature of the business. To do so, we’ll need to ease regulations and direct management tied to individual fishermen by the government.

In other words, the so-called “indirect management” issue. Currently, fishing in a fishery for a certain period requires fishing rights. You’ll have to participate in the local fishing cooperative, pay a portion of your sales, and so on, following the arrangements made by the relevant cooperatives.

What we need is for businesses and individual fishermen to receive direct quotas (allocation of catchable fish) and licenses. If this is implemented, fishermen could make their own individual sales efforts under the direct control of the government. It is generally said that the Norwegian and Scandinavian fisheries to be ideal. This is because of how their industry is structured.

They’re an all-in-one package, covering everything from production, processing, and distribution, in the way they should be as a management entity. This is why they can create a clean and well-treated working environment. As for Japan, I believe that the small-scale nature of fishermen who only catch fish hinders the sustainability of individual fishermen.

There were nearly one million fishermen when the indirect management system was formed. It’s difficult to assign so many fishermen just whatever area individually. However, there are only 140,000 to 150,000 fishermen nowadays. The situation is changing, and I believe the system itself should change with it.

–Can you tell us more specifically about the possibilities for implementing IT and digitalization, as you mentioned at the beginning of this article?

I believe that digitizing fixed-net fishing will make it more selective. Izumisawa Suisan is currently working on two digitization projects.

First one is digitizing landings for catch reports. We would like to be able to automatically manage data on all landing figures sent from every fishing ground.

As a fisherman who uses fixed nets, I’ve always wanted to know where the many parts of the net are in real-time.

For example, a single net is divided into many parts. This includes the dredging, climbing net, the playground, each part being placed in a different location. It would be nice if those fishing nets and vessels could be tagged and displayed on Google Maps so we could see their location.

If this is realized, there will be no need for vessels to call each other while working to check each other’s work and the location of fishing nets. Fishermen can then see with a single smartphone where the boat that raises the nets is and which warehouse the recovered nets are being managed.

–It will definitely be easier to manage all the fixed nets at once.

Furthermore, I’d also like to link the fish finder data for each fishing ground with the landings’ data management. It would be interesting to learn over time the species and number of fish caught during each trip. For fixed nets, we would accumulate data on fish landed at certain locations, times of the year, and times of the day.

This will allow fishermen to automatically predict how many tons of sardines, mackerel, and other fish can be expected to be landed in the fishing ground before the nets are raised. If the accuracy is improved, fishermen would be able to predict when to avoid raising the net when they’re likely to catch a species with a huge quota. Conversely, they can also actively raise the net when predicting a species with a surplus. In terms of resource management, this will also enable fixed-net fisheries to address the problem of not being selective enough.

If this is realized, going offshore to catch fish will be a momentary task. I hope it will become the job of fixed-net fishermen to spend time managing fishing gear and other work arrangements.

–It looks like fixed-net fishing still has plenty of hidden potential.

Fixed nets also have their own unique advantages.

Simply speaking, fishermen will have more time for their personal lives, allowing them to sleep at home. Other fishing methods inevitably lead to a special lifestyle, such as living on the boat and setting sail late at night.

Meanwhile, fixed-net fishing allows the fisherman to both fish and go home within the day. You’ll only need four hours in the morning if all you’re doing is hauling out the net and landing the fish. If you look at the fish finder, and there’s no fish, you won’t need to operate.

If we could simplify the job of fixed-net fishermen, make it a little more manual, and eliminate the need for specialized skills, various kinds of people would be able to enter and find employment. I believe fixed-net fishing to be one of the few fisheries that could achieve this.

Other countries do not define an occupation as a lifetime commitment. That’s why, same in Japan, for example, while you’re young and physically capable, you can even choose to work at sea for 10 years because the salary is very high. This is a situation I aim to create.

Hiroshi Izumisawa

CEO, Izumisawa-Suisan Co. Ltd.

Familiar with fixed nets from his family business since he was a child, helping raise fish hauls as an elementary schooler. When he took over the business, he expanded it outside Iwate Prefecture, currently managing nine fixed net fisheries and selling fresh marine products. Mainly operates in Onagawa Town and also does business in the Hokkaido region and Iwate, Miyagi, and Shizuoka prefectures. He is known as a leading figure in the fixed-net fishing industry, having participated in the Council for the Promotion of Regulatory Reform regarding the revision of the Fishery Law.

-1024x606.png)

_-1024x606.png)

1_修正524-1024x606.png)

.2-1024x606.png)

2-1024x606.png)

-1-1024x606.png)

Part2-1024x606.png)

Part1-1024x606.png)