On October 19th, 2022, stock management project of hard clam fishery in Aso Sea, Kyoto was selected as the champion in the U-30 category of the 4th Japan Sustainable Seafood Award. This category was newly established this year to recognize the efforts of organizations and individuals under 30 years old.

The population of “hon-hamaguri” (hard clam, Meretrix lusoria) has declined rapidly throughout Japan. Even in Aso Sea in Kyoto, the catch of hard clam has been on the decline ever since it peaked in 2002. In the midst of all this, Junya Murakami, a fisherman from Aso Sea in Kyoto, wanted to continue his beloved work as a fisherman in the sea that he inherited from his grandfather, prompting him to call for Kyoto Fisheries Cooperative to implement stock management of hard clam when he was 22 years old.

He then launched a hard clam stock management project in 2021 in collaboration with Steering Committee of Mizoshiri area of Kyoto Fisheries Cooperative and the Fisheries Technology Department of the Kyoto Prefectural Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries Technology Center, following a self-imposed fishing ban of two years from 2019. Drawing on the advice of the Fisheries Technology Department, the project aims to facilitate the stock recovery of hard clam by designating fishing seasons, regulating operational hours, limiting the catch of hard clam harvested, and ending a fishing season once the stock reaches 30% to 40% of its initial figure, instead of relying on previous limits on the length of hard clam.

Nao Nagasawa, an intern at Seafood Legacy who is of the same generation as Murakami, spoke to Murakami about the background of this project, what he hopes to see from the fishing industry moving forward, and more.

Junya Murakami

Junya Murakami (25 years old) was born in Kyoto Prefecture. He has been fishing in the Aso Sea since his grandfather took him there at the age of 3. After graduating from junior high school, he achieved his dream of becoming a fisherman and started his own business at the age of 19. As the youngest fisherman in the Mizoshiri area, he fishes with a variety of fishing methods, including Aso Sea gill net fishing, shellfish digging, longline fishing, and pole-and-line fishing.

When he was 22 years old, he appealed to Steering Committee of Mizoshiri area of Kyoto Fisheries Cooperative regarding the need to implement stock management of hard clam and subsequently worked with the Fisheries Technology Department of the Kyoto Prefectural Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries Technology Center on a stock recovery project. He also seeks to improve the quality and value addition of fish by refining the shinkei-jime (nerve tightning) technique of slaughtering fish, etc.

――Congratulations on your award. Firstly, please tell us more about your motivation behind working on this stock recovery project.

Junya Murakami (henceforth, “Murakami”): To put it simply, it’s because the population of hard clam has visibly declined. I knew that its population had been declining back in the day, but it has declined further since then.

To begin with, the Aso Sea is a sea where fishing is impossible without bivalves. Short-neck clam, ono-gai (soft-shell clam), and hard clam all used to be abundant in the past, but the catch of short-neck clam and onogai have gradually declined. Fishermen who had been harvesting these two species of clams began to catch hard clam instead, which dramatically accelerated its rate of decline. All that happened in the blink of an eye.

We launched this project after it dawned on me that hard clam, which is the last survivor among these bivalves, is also under threat.

――Around when did it start to become difficult to catch bivalves in the Aso Sea?

Murakami: My grandfather was an active fisherman when I was in elementary school, and he would catch around 20kg per day. His buckets were filled to the brim with clams, to the point that there were more short-neck clams than sand. Unfortunately, the decline in catch has not stopped, and this year, zero catch was reported for short-neck clam in the joint area that encompasses the neighboring bay for the very first time. Since it’s necessary to test for shellfish poison when catching clams, I believe a decision was made not to catch short-neck clams, considering the cost of the test.

We used to catch 50 to 70 hard clams per day around six years ago, but this figure has dropped suddenly to 10 to 20 per day since around four years ago.

――I understand that you’ve been fishing with your grandfather since you were a child. Was there anything that left a deep impression on you?

Murakami: I remember my grandfather used to tell me not to catch the small shellfish and fish. Although he could catch sardines and do many other things, catching short-neck clams was his main work. However, the catch of short-neck clams was already declining even at that time, and my grandfather started to take an interest in stock management. He even prepared samples of different sizes of short-neck clams and told others not to catch small shellfish and fish, but his words fell on deaf ears at the time.

Still, my grandfather took it upon himself to continue protecting the stock, including by making nets that would allow small fish to escape. Having witnessed his efforts firsthand, I became convinced that was the obvious thing to do.

Junya Murakami (left) and the author (right) after the 4th JSSA (Japan Sustainable Seafood Award) award ceremony

Junya Murakami (left) and the author (right) after the 4th JSSA (Japan Sustainable Seafood Award) award ceremony

――It sounds like you’ve always had an eye on stock management.

Murakami: That’s right. Even though it isn’t a cooperative-wide practice, it was obvious as far as we were concerned that we should be letting small fish and shellfish go for species such as the blackhead seabream, sea bass, short-neck clam, and so on. I don’t feel that it’s anything special.

――Is there anyone who’s around the same age as you among those in the fishing industry in the Mizoshiri district?

Murakami: I’m the youngest, and I think my father is closest in age to me. Most of my classmates have left our hometown, so pretty much only those with presbyopia are left.

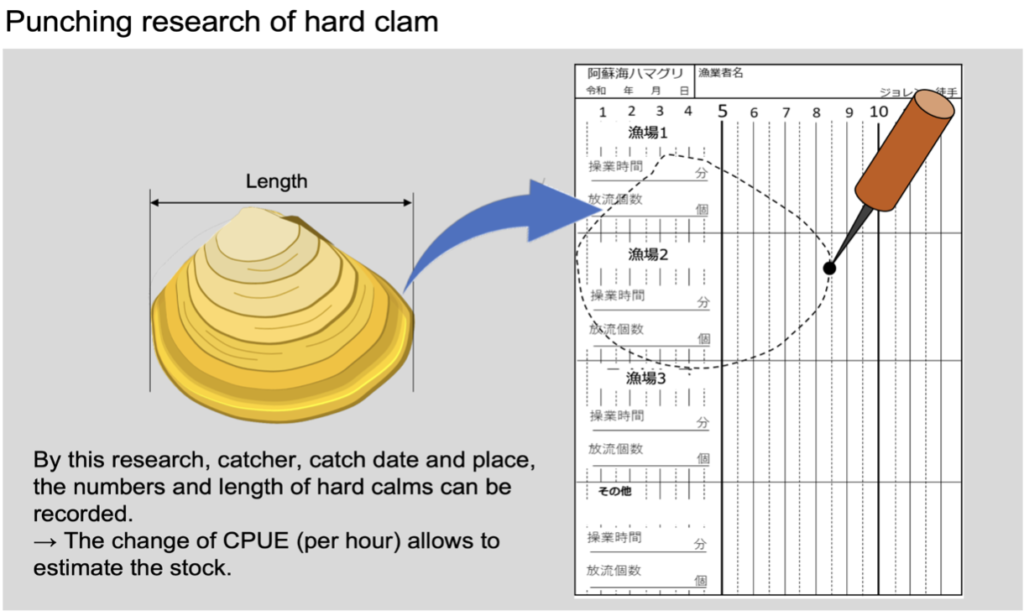

――I see. I understand that in order to estimate the stock of hard clam, people in the Mizoshiri area have been doing something called punching, where they place the clams on backing paper and punch holes to mark the maximum length of their shell so that the catch information can be recorded.

Murakami: That’s right. Everyone says that punching is a lot of work, but they are supportive of the project. They are getting involved perhaps because they feel that any growth in the stock of hard clam, no matter how small, is a good thing.

I know there are some people who say they want to catch clams every day, but at the same time, I know those who complains about catch scarcity thank me for starting stock management behind the scenes.

(Figure courtesy by Mr.Murakami, translated by Ssafood Legacy)

(Figure courtesy by Mr.Murakami, translated by Ssafood Legacy)

――Have you encountered any difficulties while working on this project?

Murakami: I haven’t personally encountered any difficulties. (laugh) Certainly, there was some pushback against the idea at the 2019 general meeting of Steering Committee of Mizoshiri area of Kyoto Fisheries Cooperative, when we first called for stock management. However, there were also quite a lot of people who were curious and listened to what we had to say. The Steering Committee then submitted a stock management request to Kyoto Prefecture, which allowed us to receive support from the Fisheries Technology Department of the Kyoto Prefectural Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries Technology Center (henceforth, “the Fisheries Technology Department”). Since the Aso Sea has a close relationship with Kyoto Prefecture, the recommendations of Kyoto Prefecture were readily accepted.

――Why does the Aso Sea have a close relationship with Kyoto Prefecture?

Murakami: There are many reasons for this. To begin with, the Aso Sea is a highly enclosed sea separated from Miyazu Bay by Amanohashidate. Because of this unique trait, we often received requests to conduct various surveys. In addition, baby short-neck clam clams are sold here, but because almost no fisheries cooperative associations carry them in the first place, we need to rely on Kyoto Prefecture for everything from catching and sorting these juvenile clams to the expansion of sales channels.

――How did you come to receive support from the Fisheries Technology Center for this project?

Murakami: The stock management of sea cucumbers was previously already underway in Miyazu Bay, which lies on the opposite side of the Aso Sea where we fish. The catch of sea cucumbers had also declined dramatically, which prompted the Fisheries Technology Department to implement stock management seven years ago.

The person in charge of stock management at that time was relatively close to my age, so we got along very well. When I approached him regarding the urgent need for the stock management of hard clam, we were able to discuss specific policies, etc.

Original Japanese text: Nao Nagasawa

-1024x606.png)

_-1024x606.png)

1_修正524-1024x606.png)

.2-1024x606.png)

2-1024x606.png)

-1-1024x606.png)

Part2-1024x606.png)

Part1-1024x606.png)