The UN Food Systems Summit held in New York in September 2021 demonstrated the importance of treating foods, including seafood, as “systems” in order to make the conversion to sustainable food systems. The Center for Global Commons (CGC)* at the University of Tokyo is also an institution that was established with the goal of improving food systems.

Naoko Ishii, Director for CGC, was appointed CEO of the Global Environment Facility (GEF) in 2012 after working at financial institutions in Japan and overseas. After completing her tenure at GEF in 2020, she was appointed an Executive Vice President at the University of Tokyo, a professor at the University’s Institute for Future Initiatives, and Director for CGC.

We spoke with Dr. Ishii, who continues her activities at the forefront of protecting the global environment, about what led to her interest in sustainability and about SeaBOS, in which she participates on the Board of Directors.

Naoko Ishii

Dr. Naoko Ishii is a professor and executive vice president at the University of Tokyo, where she is also an inaugural director for the Center for Global Commons, of which mission is to catalyze systems change so that humans can achieve sustainable development within planetary boundaries. She is of a view that academia can and should play an active role in mobilizing movements with policymakers, business and civil society towards a shared goal of nurturing stewardship of the global commons; stable and resilient planetary earth system. Under her vision, the Center for Global Commons has been collaborating with reputable international research institutions in the area of sustainability, and launching projects with Japanese business focusing on energy transition, food system, and circular economy.

Before joining the university in 2020, Dr. Ishii served the Global Environment Facility (GEF) as CEO and chairperson. During her tenure of 2012 to 2020, she formed GEF’s first mid-term strategy, GEF 2020, focusing on the transformation of key economic systems and collaborating with multi-stakeholder coalitions. She holds a B.A. in economics and a Ph.D. in international development, both from the University of Tokyo. She published several books among which two are awarded by academic prizes.

— In 1981, you joined the Ministry of Finance. After working for the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank, in 2012 you became CEO of the Global Environment Facility (GEF). What triggered this interest in sustainability?

At the time I first joined the Ministry of Finance, I think interest in sustainability was low worldwide. I had no familiarity with the topic.

I took an interest in sustainability when I was invited to respond to the open call for CEO of GEF in 2012. Around 2010, I began looking into global environmental issues. Doing so, I was hit with one scientific finding after another, and was shocked to find that the global environment had been driven to the wall. It was a further shock to learn that the Ministry of Finance (and myself within it), the IMF, the World Bank, and other financial bodies, and even society as a whole, had paid next to no attention to the global crisis.

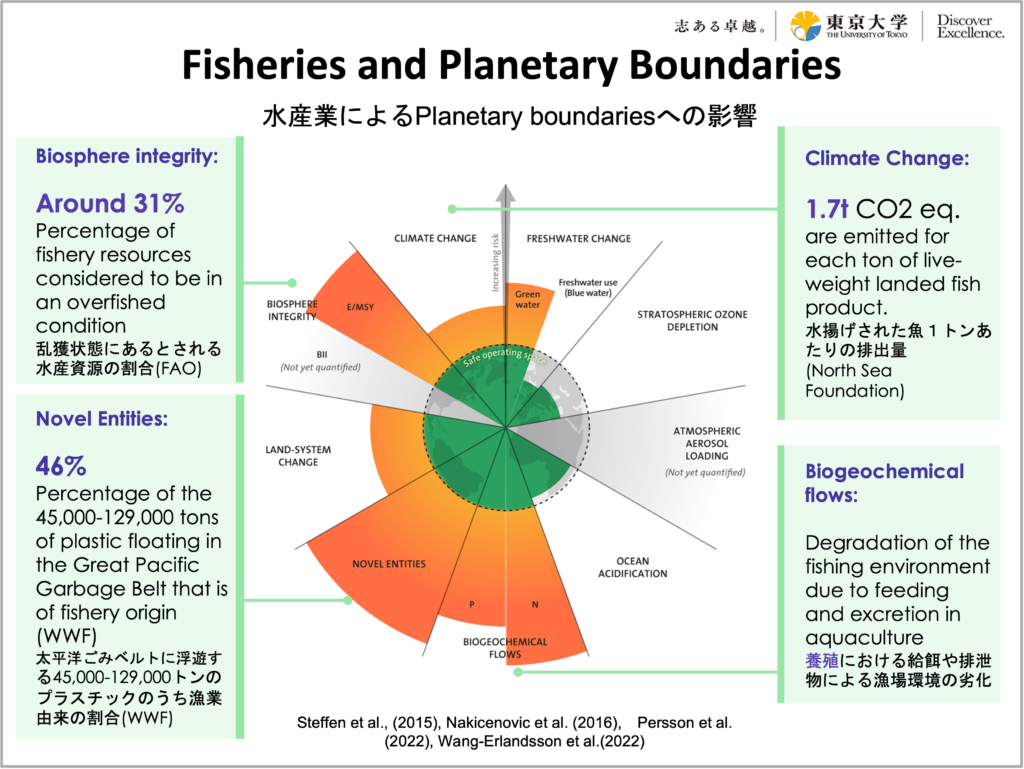

The impact of the seafood industry on planetary boundaries (the area of activity in which humans can survive, and its boundary points)

The impact of the seafood industry on planetary boundaries (the area of activity in which humans can survive, and its boundary points)

The issue of sustainability gradually began to draw attention after that. This came to fruition in 2015 the form of the SDGs and the Paris Agreement at the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP21). Drawing on this undercurrent, society is gradually waking up, I think. However, it’s my feeling that Japan is not yet tackling sustainability in earnest.

— You also take part in SeaBOS, an international initiative by scientists and ten of the world’s biggest seafood companies. How did you become involved in this?

I’d been hearing about SeaBOS since preparations for its launch ramped up around 2016. The origin of SeaBOS lay in the idea that major systemic change should be possible through a coalition of keystone actors, the world’s top seafood companies that are seen as influencing the future of the industry. I was the CEO of GEF then, and the sustainability of the oceans, including fishery resources, was a key issue in my job. From this, I took an interest in the launch of SeaBOS.

I was at GEF when SeaBOS launched in 2018. At an international conference, I had the opportunity to meet SeaBOS Managing Director Mr. Martin Exel, who told me about the organization’s activities. In 2020, I finished my term at GEF and returned to Japan. In 2021, Martin asked me to become a member of the Board of Directors of SeaBOS and I agreed.

— What sort of things have you observed as a part of SeaBOS?

I’ve only been working with SeaBOS for about two years, but I think we’re finally arriving at the stage where a foundation is coming together. To take things to the point where everyone together is able to achieve what one company alone cannot, it’s necessary to foster relationships of trust, something not easily done in a short period of time. The companies in SeaBOS are all rivals, and some of them aren’t used to cooperating with rivals on things.

In Europe and the United States, companies distinguish between the pre-competitive stage and the competitive stage. Typically, in the pre-competitive stage they create industry rules and make investments together to develop the industry, and from there enter the competitive stage and begin competing. Japanese companies need to build up experience and understand this concept.

Because SeaBOS is an organization in which scientists and companies undertake activities in cooperation, building relationships of trust between the two sides is important. I hope to see the ball tossed back and forth as scientists make key suggestions regarding the oceans and companies take in and discuss those.

SeaBOS shoulders a heavy responsibility despite having not much experience in tackling issues collaboratively. As this is an important opportunity, though, I hope that it will continue doing what should be done for the sake of Japan’s seafood industry and sustainability. The issue from here on out is for Japanese companies to cooperate with each other as well as with overseas companies to advance whatever initiatives can be undertaken on behalf of the world’s ocean.

— What are your expectations toward SeaBOS in order to effect change in the seafood industry?

SeaBOS’ aim is drawing a roadmap for how the seafood industry, including consumers, can change in order to create profits while also supplying sustainable seafood to the public. If SeaBOS is able to chart the right path, that should prove beneficial to all parties concerned, including small and medium-sized companies.

SeaBOS’ role is creating rules to deal with big issues that cannot be resolved simply. As an example, the issue of IUU fishing should first be tackled collaboratively by the keystone actors in SeaBOS. Resolution by a single company or by small and medium-sized companies alone isn’t possible. I think that SeaBOS will first chart a path as necessary, after which small and medium-sized companies will consider how to proceed along that path.

Original Japanese text by: Shino Kawasaki

-1024x606.png)

_-1024x606.png)

1_修正524-1024x606.png)

.2-1024x606.png)

2-1024x606.png)

-1-1024x606.png)

Part2-1024x606.png)

Part1-1024x606.png)