Mankind is currently facing unprecedented changes in the context of our environment, resources, climate change, infectious diseases, and armed conflicts. In Part 1, we spoke to Mr. Naoya Kakizoe (Chairman of the Marine Eco-Label Japan Council), who had served in the top management of Nippon Suisan Kaisha Ltd. (hereinafter, “Nissui”) for over a decade and has been engaged with the fisheries industry in Japan and the rest of the world since his involvement in the whaling industry in the 1960s, on the various changes that he has witnessed hitherto.

(<<<Read Part 1)

In Part 2, we will speak to Mr. Kakizoe about the challenges facing Japan’s fisheries industry and the possible solutions, with a focus on the mindset that is necessary to achieve both sustainable fishery resources and a sustainable fisheries industry.

――Are fisheries in Japan undergoing a rapid decline?

It is not so much that Japan’s fisheries industry is in decline but that its structure is evolving. Our goal today is not to catch as much fish as possible but to catch the fish we need. There are also fewer fishermen and fewer vessels today. In other words, Japan’s fisheries industry has evolved from an industry centered on catching fish to one aimed at creating maximum value with fish. In that sense, I believe it is not entirely accurate to say that only Japan’s fisheries industry is in decline out of all the countries around the world.

How much fish does Japan currently need? Indeed, Japan had peaked in the mid-1980s with a whopping 13 million tons of fish caught, of which 5 million tons were Japanese sardines that were mostly used as raw ingredients for fish meal and fish oil.

For instance, when it comes to the competition between skipjack tuna pole-and-line fishing and purse seining, pole-and-line fishing vessels always say that they can catch more fish if the purse seining fishing vessels were not occupying the same fishing grounds. That is certainly true.

With regard to the coordination between fisheries, there is a cutoff in New Zealand of 20 nautical miles for offshore vessels and small coastal vessels. Vessels with large fishing capacity are not allowed inside 20 nautical miles from the coast.

However, Japan has not imposed a cutoff like this, even though many different local regulations exist. And because the fishing capacity of vessels that had originally practiced pole-and-line fishing along the coast has grown, they have started to venture further offshore, which conflicts with the interests of the purse seining fishing vessels that operate offshore.

――Is it difficult to amend those regulations in Japan?

It is rather difficult. It may be possible for pole-and-line fishing to survive if the skipjack tuna caught that way fetch higher prices than those caught by purse seining, but if consumers always choose the cheaper option because they feel that skipjack tuna is still skipjack tuna regardless of the method by which it is caught, then pole-and-line fishing may eventually vanish. Consumers make the difference at the end of the day. Personally, I believe that it would be great if both fishing methods could be preserved, especially since pole-and-line fishing is part of our wonderful fishing culture.

Pole-and-line fishing involves the use of a single fishing rod to catch skipjack tuna individually (photo courtesy of Myojin Suisan)

Pole-and-line fishing involves the use of a single fishing rod to catch skipjack tuna individually (photo courtesy of Myojin Suisan)

――What are your thoughts on how Japan can best manage its own fisheries and fishery resources?

From my personal experience in the whaling business, I have always thought that it was important to implement an IQ (individual quota) system. It would be a good idea to allocate the amount of fish each vessel could catch.

――In other words, you prefer a quota system to a”first-come-first-served” basis.

In short, I believe that we should implement a TAC (Total Allowable Catch) system, where each vessel is allowed to catch only a specified number of tons of fish. Within that quota, vessels can then determine when they would catch the fish, where and how to sell it, and how to process the fish they catch in order to fetch the highest possible price.

Landing salmon in the fall (photo courtesy of the Hokkaido Federation of Fisheries Cooperative Association)

Landing salmon in the fall (photo courtesy of the Hokkaido Federation of Fisheries Cooperative Association)

What this means is that the fisheries industry should not be one that catches fish but one that creates value. Although times have changed since a long time ago, people have not adapted their behavior accordingly. In Japan’s fisheries industry, not many chief fishermen listen to what vessel owners have to say. They often think that once they are out at sea, vessel owners should just keep quiet and let them do whatever they wish. That should not be the case.

In whaling as well, these fishermen did not abide by the instructions of the fleet captain of the motherships and caught whatever they wanted. As the quota system became one that allocated quotas by country, by whale species, and eventually by sea area, one management-related idea that emerged in these increasingly challenging circumstances was to listen to the input of the chief fishermen, or in other words, have these chief fishermen think about management. To this end, fleet meetings started to be held every year prior to the fishing season, where all parties involved come together to disseminate the guidelines.

You might say that this is specific to the whaling industry and that things would be different with skipjack tuna. But to put it simply, we need to have a TAC system that serves as an IQ system with strict allocations, and fishermen would have to figure out how they are going to catch fish within the allocated quotas. In fact, it would be even better to decide on the sea area, but I am not sure if we can go that far with the current stock management data available. We did ultimately reach that stage in the case of whales. After all, stock management is a difficult task, but I believe the stock populations of whales are probably growing.

――In Japan as well, there is a belief that the rigorous implementation of stock management will result in sustainable resources.

That is indeed the objective of the amended Fisheries Act. However, there are management-related difficulties. There was recently a newspaper article about rockfish, which is caught in multiple fishing grounds whose fisheries are not necessarily on good terms with one another. In the fisheries industry, neighbors are often enemies, something that has been true since the Edo period, so there are always management-related challenges.

――However, it is possible to impose allocations if the will to do so exists.

It is not possible for the government to do everything. I believe that voluntary management spearheaded by fisheries cooperatives, etc., is a superior aspect of stock management as it is practiced in Japan.

――From the perspective of consumers, it is difficult to tell if a seafood product is sustainable. It would certainly help if more products were tagged with eco-labels such as MSC and Marine Eco-Label Japan (MEL).

Around 5% of Japan’s aquaculture and fisheries catch is currently certified by MEL alone, while around 10% of catch around the world is certified by MSC. Children tell me when I give classes at schools that they have learned they should buy fish with labels, but their mothers only look at the price when choosing fish (laughs). Fish tagged with eco-labels may be a little more expensive, but it is not inordinately expensive. Consumers who purchase fish with eco-labels contribute to Goal 14th of the SDGs (“protecting our vibrant seas”), and therefore, this can be thought of as our collective responsibility as far as consumption is concerned.

An Ito-Yokado storefront featuring MEL-certified products (photo courtesy of Ito-Yokado)

An Ito-Yokado storefront featuring MEL-certified products (photo courtesy of Ito-Yokado)

The Seven & i Group carries MEL-certified products at all its stores, including Ito-Yokado, York, and York-Benimaru. Therefore, when it imports yellowtail fillets, all yellowtail products sold at the store can be tagged with eco-labels regardless if they are sliced or sold as sashimi. Things become very different once retailers start doing that, and when this trend spreads to restaurants, it will grow into a big movement.

Yokohamaya-Hompo Shokudo promotes the use of sustainable seafood by featuring MEL-certified products on its menu (photo courtesy of the Marine Eco-Label Japan Council)

Yokohamaya-Hompo Shokudo promotes the use of sustainable seafood by featuring MEL-certified products on its menu (photo courtesy of the Marine Eco-Label Japan Council)

――Given the variety of international certifications such as MSC, what is the significance of pushing for a seafood eco-label that is based in Japan?

The basic concept of eco-labels originated from rather countries in the northern hemisphere. For instance, in both Iceland and Norway, the top few fish species account for around 80% to 90% of their catch.

What about Japan? When I was working at Tsukiji Market in the past, I found that there were around 1,200 species of fish in commercial distribution each year. We have a vibrant food culture that comprises a wide variety of seasonal fish across different seasons as well as a complex distribution system that supports this culture. Shouldn’t we make an effort to preserve this diversity?

Until now, many people, including the government, have viewed diversity negatively because it amplifies micro-differences and hinders productivity. However, I do not think that is true because in the case of Japan, it is a superior attribute that cannot be imitated by other countries.

The seafood eco-label is a mechanism that seeks to ensure traceability. We started this journey with global standards, but from the point of view of Japan’s fisheries industry, it is more desirable to have an eco-label that can protect our own industry and our national interests. Without a certification system like this, we have no way of protecting Japan’s food culture and the uniqueness of our fisheries industry.

Stock management in Japan is unique for how it integrates government-directed management with voluntary management. In a sense, Japan’s unique approach might be perceived as a cop-out. Some people say that voluntary management is an absurd idea, but if we look around the world, it is not an unusual practice by any means. At the same time, some people have argued that the implementation of an IQ system would diminish the advantages of voluntary management, and there is a need to grapple with how voluntary management can be carried out in the context of IQ.

――We are currently in a transitional period where the Fisheries Act has only been recently amended and the Seafood Distribution Regulation Act will only enter into force in the future. What are your views on the current state of Japan’s fisheries industry?

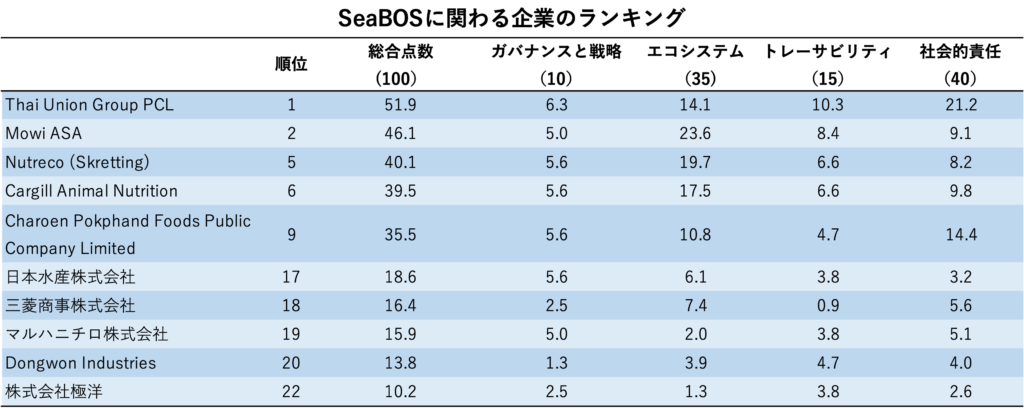

The Seafood Stewardship Index of the WBA (*1) selects the top 30 seafood companies in the world and ranks them by grading them according to the criteria of governance, ecological impact, traceability, and social responsibility. In first place is Thai Union, and in second is Mowi, a Norwegian salmon-farming company. Looking at the top ten companies of SeaBOS, we see that Skretting is in fifth place and Cargill is in sixth, both of which are fish feed companies.

Nissui is in 17th place, Maruha Nichiro is in 19th, and Kyokuyo is in 22nd. Mitsubishi Corporation, the parent company of SeaBOS member company Cermaq, is ranked 18th (*2).

The numbers in parentheses indicate the perfect scores for the respective criteria. Mitsubishi Corporation is the parent company of Cermaq, a SeaBOS member company.

The numbers in parentheses indicate the perfect scores for the respective criteria. Mitsubishi Corporation is the parent company of Cermaq, a SeaBOS member company.

――Japanese companies seem to be on the lower end of the rankings.

That’s right. SeaBOS member companies are pretty polarized. What I am saying is that these rankings should not simply be ignored. For instance, how does a company make a decision to commit to sustainability efforts and how does it communicate its intention globally? If we ignore these rankings after they are released, they will continue to stay that way. In other words, I believe that it is vital to actively communicate the necessary information.

I also believe that the IUU Fishing Index should not be ignored. Japan is also not doing well in that index. Of the 152 countries around the world, Japan is ranked 19th from the bottom in terms of its IUU fishing risk. As for the skepticism among American and European NGOs regarding Japan’s transparency and their distrust of how Japan is handling its IUU fishing risk, these are not things that we can afford to ignore. If there are areas of difference, we should articulate these differences. By the way, the three lowest-ranked countries are China, Taiwan, and Cambodia.

For instance, unreported tuna was discovered in Oma in the last two years. There was also a case in Yaizu of skipjack tuna being distributed illegally without having been weighed, as well as many instances of issues with the so-called labeling of production areas. Trust in Japan’s fisheries industry is greatly damaged each time issues like that come to light.

――So it is true that Japan is plagued with these issues.

It is true that these issues exist in Japan, but it is still a stretch to say that out of the allocated quota of thousands of tons of bluefish tuna for the entire Japan, Japan’s IUU Fishing Index score is destroyed merely because of the 60 tons of unreported tuna in Oma.

――What do we need to do for the future of Japan’s fisheries industry?

The question that needs to be asked is who actually owns the fishery resources. Under our Civil Code, fishery resources are considered ownerless property, and the rights to these resources only arise after the fish is caught. However, fishery resources belong to the country, or rather, the people of the country. Yet, this perspective is not captured in the Fisheries Act, which makes it seem like they belong to fishermen. This had been decided in 1741 during the Edo period, and although an attempt was made during the Meiji period to reform the law, it did not happen and remained that way for a long time.

Mr. Kakizoe discusses the issues and solutions for Japan’s fisheries industry. His words serve as a powerful reminder that although Japan has the resources, nothing can be done if it lacks the industry. (Photographer: Miki Yamaoka)

Mr. Kakizoe discusses the issues and solutions for Japan’s fisheries industry. His words serve as a powerful reminder that although Japan has the resources, nothing can be done if it lacks the industry. (Photographer: Miki Yamaoka)

――In other words, a fundamental change is necessary.

The problem is that if someone illegally distributes skipjack tuna caught in Yaizu, they are considered a thief, but those who catch fish from the sea before they are supposed to are not considered thieves. Isn’t there a problem with the fact that people have been catching these “ownerless” fish for decades and centuries?

――Indeed, the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea contains the phrase “the common heritage of mankind.”

That’s right, “the common heritage of mankind” refers to the common heritage of the people of each country. People have to manage the fish within the exclusive economic zone that extends 200 nautical miles beyond their country’s territorial sea because the management of the fish in this area is the responsibility of the country in question. Given that Japan has ratified the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, our law really needs to be amended. I think that it is too irresponsible to regard these resources as “ownerless.”

Once it is properly decided how fishery resources, which are the common heritage of the people, can be caught, all that is left are economic deliberations. If, for instance, an IQ system is implemented, the people allotted the IQ will adopt the best course of action. This allows the fisheries industry to transition from one that catches fish to one that creates value.

――What kind of value will the fisheries industry create?

Although delicious flavors are indeed a form of value, we also need to think more about social value moving forward. For instance, our world is becoming a place where people purchase fish with eco-labels because they wish to play a role in contributing to the SDGs. In other words, we need to participate in the creation of social value. It is imperative for us to ensure that there is still fish and that Japan’s fisheries industry remains viable in our children’s generation.

Although Japan has the resources, nothing can be done if we lack industry.

――Ensuring the sustainability of both fishery resources and the fisheries industry is a difficult task.

It is indeed difficult, but we will never resolve the problem if we continue sweeping it under the rug.

――What do you think is important when it comes to promoting sustainability efforts?

In short, I think every Japanese citizen should think of sustainability as their personal responsibility. This is because the problems confronting our earth are exemplified by what is happening to our fisheries. We could even say that these are problems that threaten our children’s future, and perhaps even our own immediate future.

Naoya Kakizoe

Naoya Kakizoe graduated from the Tokyo University of Fisheries and joined Nippon Suisan in 1961, where he served as President & Representative Director from 1999 to 2013. During this time, he also served as Vice Chairman of the Japan Fisheries Association, Chairman of the Japan Frozen Food Association, Chairman of the Japan Association of Refrigerated Warehouses, Chairman of the Association of the Safety of Imported Food, Japan (ASIF), and Chairman of the Japan Food Industry Association. In 2016, he was appointed Chairman of the Marine Eco-Label Japan Council.

Original Japanese text by: Chiho Iuchi

-1024x606.png)

_-1024x606.png)

1_修正524-1024x606.png)

.2-1024x606.png)

2-1024x606.png)

-1-1024x606.png)

Part2-1024x606.png)

Part1-1024x606.png)