Poaching of abalone, sea cucumber, and other fishery products by non-fishermen has become a problem in recent years. This poaching continues to grow, while catch volume by fishers undergoes a significant decline.

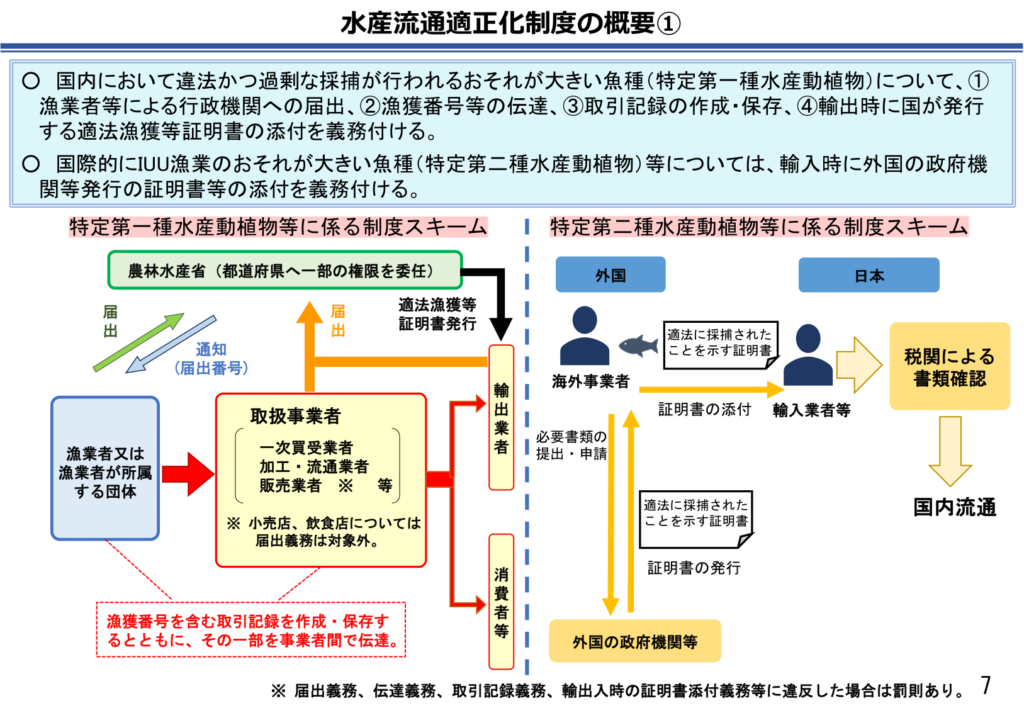

An act to prevent such poaching, the Act on Ensuring the Proper Domestic Distribution and Importation of Specified Aquatic Animals and Plants (hereinafter “Domestic Trade of Specified Aquatic Animals and Plants Act”), was promulgated in December 2020 and is scheduled to enter into force in December 2022. This act mandates the communication and recording of information among businesses to verify that fishery products do not originate in poaching or other IUU (illegal, unreported, unregulated) fishing. The act covers a wide range of domestic and imported fishery product activities, including production, processing, and distribution, and can be seen as drastically reworking the distribution of fishery products, which has so far been unregulated.

We spoke with Masaharu Amano, head of the Fisheries Processing Industries and Marketing Division of the Fisheries Agency. He spoke about the expected effects of enactment of the Domestic Trade of Specified Aquatic Animals and Plants Act, and the future that the act envisions for fisheries.

— Please give us an overview of the Domestic Trade of Specified Aquatic Animals and Plants Act.

The act has three main points. First, fishermen, primary wholesalers, distributors, and processors who handle specified aquatic animals and plants that are often illegally caught are to provide notification to the government. Second, “catch number” will be attached to fishery products to convey information among operators in the supply chain. Third, transaction records are to be created and saved.

Through these actions, it will be possible to grasp the real state of operators and certify that fishery products handled by these have been properly caught. The act will also ensure traceability, from production to sale.

— Why is this act needed?

Poaching by non-fishermen is rampant in Japan today. There are also risks that so-called IUU fishery products are slipping into imported products. IUU fishing, including poaching by non-fishermen, contravenes the spirit of stock management that is essential to the pursuit of sustainability in the seafood industry and involves fishermen who properly fish in unfair competition. Consumption of these commodities ultimately leads to our providing support for IUU fishing. The act was enacted to put an end to this structure and to create a world in which fishermen, distributors, and consumers can connect with the peace of mind.

Unfortunately, it cannot be said today that no illegally caught fishery products are reaching consumers. Japan is one of the leading consuming countries of fishery products and is the world’s fourth-largest market for imported fishery products after Western countries. We believe that, through this act, we should carry out our duty to stop the inflow of illegal fishery products and leave the bounty of the sea in an abundant state for future generations.

To begin with, the reason why poaching has increased so much is the notable advance of equipment for fishing, including diving equipment and GPS functionality. In short, poaching has become easier for non-professional fishermen. Populations have declined in coastal areas, too, making it easier for people to come in from outside. The increase in poachers will significantly impact stocks. We need to take firm action here.

Abalones that attach to rocks are easily targeted by poachers.

Abalones that attach to rocks are easily targeted by poachers.

— What has been the reaction of concerned parties to the act?

At briefings, many of the reactions we initially receive are that the system is difficult and will be a heavy burden. For fishery cooperatives that operate local markets, there will be the work of issuing catch ID, which was not required before. Processors will also need to perform management for each ID. They should feel that it will be a burden at first.

In rice and cattle, for which product traceability is ensured in a similar way, problems existed with tainted rice and bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), which led to strong demand for traceability from consumers. For fishery products, however, cooperation will take place not as a consumer initiative but as a responsibility placed on producers and distributors. Under these circumstances, it was quite difficult to gain an understanding of the concerned parties.

— What effects can be expected from the enforcement of the act?

It is important to consider the effects together with the Fisheries Act. The Fisheries Act that was amended in 2018 introduces strict punishments for poachers, including the imposition of up to 3 years of imprisonment and up to 30 million yen in penalties. Poachers will naturally look for loopholes to escape this punishment. The new act makes distribution channels visible and will be able to block loopholes used by poachers.

Until now, it has been difficult to crack down on goods already in distribution. Poached fishery products may be mixed in at a variety of locations, but it was impossible to investigate them a blind way. Once the act enters into force, however, we will be granted the authority to conduct on-site investigations.

Notifications by operators are also important in these investigations. Until now, we were unable to see how many sea cucumber processors there are, or where they are. All of these things will become visual, and operators who have not filed notifications will be charged with violating the obligation of notification.

Effects from whistleblowing can also be expected. There is a non-binding obligation to report persons engaging in illegal acts. Any such report will trigger an investigation by authorities, so we believe that many cases will be uncovered.

While there are difficult areas, we believe that we could get a good result once these have been overcome. Digitizing information will help to lighten the everyday burden, so we plan to provide support for this. As the seafood industry has been slow to digitalize, achieving this should lead to major reforms in fishery product distribution.

When we talk to people in the field, they tell us that no problem exists as they buy from trusted suppliers. However, the possibility that poached fishery products get mixed in somewhere is undeniable. Poachers scoop up large volumes of catch at a time. If slow-growing benthic organisms are uprooted, stocks will eventually become depleted. Without cooperation from distributors, we may lose our means of earning a living in the future. With such images in mind, we are asking for cooperation.

— It is said it took the act over two years to go from conception to enactment. What sort of points did you struggle with?

Little information was available about fishery distribution. Until now, the Fisheries Agency had no legally-backed authority over distributors, and there was no way to assess the state of distributors. Under these circumstances, we listened to people in the industry, formed hypotheses, and put together a system from the ground up.

In creating the act, we referred to precedents in Europe and the US. However, our impression was that even there, systems did not have a very long history, and they are operating the system with some uncertainty. In addition, the fisheries product distribution structure is more complicated in Japan. It was tough to create a new act amid a complicated situation that we couldn’t fully grasp.

In the end, though, the act passed the Diet unanimously. I feel that there’s great significance in that this decision on what should be done has been made by ruling and opposition parties alike.

— What sort of discussions took place before the act was created?

One area was the matter of coverage. The act is currently aimed at a wide range of parties, but there were initially proposals to narrow down the act’s targets. For example, there was the suggestion that if fishery products in local markets are shown to have been properly caught, it would be unnecessary to continue strict supervision from that point forward.

However, the stage of distribution at which poachers release fishery products cannot be known. Will it be the market, the processing plant, or the stores? In response to this, the idea came out that supervising everything would be necessary, and so the current form took shape.

Another major issue was which fish should be given catch ID. This has not been decided at this stage; we plan to make a decision after talking to all concerned parties. As the starting point is the prevention of IUU fishing, including poaching by non-fishermen, the study group held discussions on setting domestically caught abalone and sea cucumber, and imported squid, as the initial targets.

Another discussion concerned whether to inform consumers, that is, whether to place the catch ID on products alongside the product name and place of origin. There was active debate over this, too. However, considering the priority, it was decided that this was not needed at present, as it would be sufficient to confirm proper catch up to the point of retail where consumers are certain to purchase the products.

— Could you tell us about your personal career?

After joining the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, I was initially involved in food distribution. In my sixth year with the Ministry, I was assigned at one point to the Fisheries Agency. There I became involved for the first time with the Fisheries Basic Act, which exerts influence in a number of directions, and I found the difficulty and the attractiveness of creating systems.

After that, I was involved in work to abolish government wheat purchasing, a major structure remaining in the Act for Stabilization of Supply Demand and Prices of Staple Food. Abolishing this went through difficult coordination with concerned parties, from the viewpoint of strengthening production sites. I then became involved in the promotion of Japanese foods registered as UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage, and the promotion of agriculture, forestry and fishery product exports. After that, I returned to the Fisheries Agency for the first time in 15 years.

— Given your experience in a wide range of fields, how do you feel about your current mission at the Fisheries Agency?

My hobbies are diving and fishing, so I like the ocean. People in Japan eat a lot of fish and the ocean is familiar to them. I was involved in the promotion of Japanese food, and I considered Japan as a leader in the area of fish. However, when I was assigned to the Fisheries Agency again, I found that regulations lagged a bit behind Europe and the United States, which could disadvantage exports and lead to depletion of fishery resources. Studying the background to this, I realized that there were areas where the Fisheries Agency had to work harder. So, I decided to do my best where I could.

Within the Fisheries Agency, the Fisheries Processing Industries and Marketing Division is involved in all kinds of work, from when fish are landed to when they are eaten. The government tends to devote resources to production areas, such as fishing and aquaculture, but from a business perspective, the business that spans landing to consumption is larger. However, those parts had been left to the private sector. Incorporating these reflections, the Domestic Trade of Specified Aquatic Animals and Plants Act was created. I really look forward to seeing how our work will change with the passage of this act.

— Heading into enforcement of the act in 2022, what actions are planned?

First, we plan to move ahead with discussions of the fish species to be given catch ID. After that, we will begin considering how to digitize the transmission of information.

Until now, the system of fishery cooperatives was managed separately by individual system companies, as the means of catch and names of fish differ by fishery cooperative. The enactment of the act, however, should enhance cross-functional management of the system. When this has been done, the digitization of the seafood industry may progress at an amazing speed.

We received comments from the field stating that entering information into computers is a hassle. In the future, however, voice input and communication may be possible. If that happens, they could communicate quicker than the conventional way of writing on paper.

Using a voice entry system to record info as it is will fulfil the obligations imposed by the new act. It would also be good if such systems were not expensive and could be used anywhere.

— In closing, please tell us what you hope to focus on from here on out.

I want to put more effort into distribution and processing, which have not been given much attention so far. For decades, the problem has been that of things being made but going unsold and being wasted. The structure has been one of “this is what was made, so eat this,” with production and processing that does not reflect the opinions of consumers.

I think that distribution and processing will play major roles to improve this structure. This is because distribution has the function of communicating consumers’ needs to producers, and processing has the function of making products convenient for consumers to eat. Domestic Trade of Specified Aquatic Animals and Plants Act will also serve as a tool for strengthening this distribution.

Enforcement of the act may bring about further development of freezing technology and thawing technology, and AI-based automation may advance as well. In terms of exports, compliance with the Act will create the advantage of making products easier to distribute in foreign countries, which require the presentation of transaction records. I want to focus on initiatives to increase exports.

As dining out declines under the COVID-19 pandemic, how fish is consumed at home is also a topic. Consumption at home faces the hurdle of the time and effort required for filleting fish. I want to devise ways to lower that hurdle and make efforts to change the product itself.

A lot of different elements come together in the distribution and processing of fishery products, embracing great potential. With the enforcement of the Domestic Trade of Specified Aquatic Animals and Plants Act, I hope to generate more vitality in this field.

Masaharu Amano

Director of Fisheries Processing Industries and Marketing Division of the Fishery Agency.

Masaharu started working at the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries in 1995. He entered the Fishery Agency in 2000 and was working on the enactment of the Basic Fisheries Act. From 2005, he was working on a partial amendment of the Food Act. Since he was assigned to Management Improvement Bureau Finance Division, he has been in charge of overall financial projects in the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, including the 2008 global financial crisis. After that, he led agricultural or seafood promotion as a Private Secretary to Minister and Export Promotion Group Leader. He started his current career in July 2018.

-1024x606.png)

_-1024x606.png)

1_修正524-1024x606.png)

.2-1024x606.png)

2-1024x606.png)

-1-1024x606.png)

Part2-1024x606.png)

Part1-1024x606.png)