Founded in 1882. With its headquarters in Kesennuma, Usufuku-honten is a fishing company specializing in longline pelagic tuna fishing, and Sotaro Usui is it’s fifth-generation representative. The company has a total of seven vessels and operates in the Atlantic Ocean. Three are stationed in Kesennuma, three in South Africa, and one in Spain.

In addition to carrying out operations with strict resource management, the company also launched a “organization for the promotion of Kesennuma fish in school lunches” project to incorporate these fish into the lunches of children in local schools and worked with the nendo design office to develop a vessel which crew can live on comfortably. These are just a portion of the initiatives it is involved with.

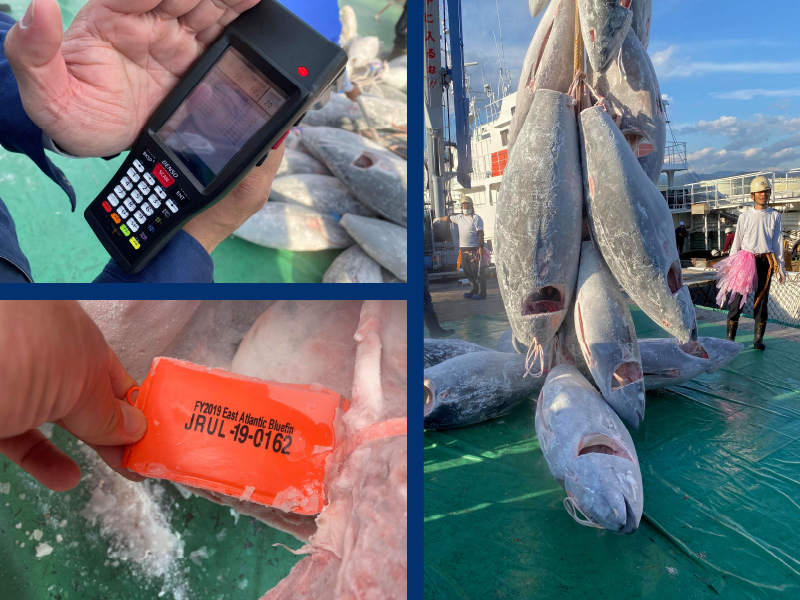

In August 2020, the Atlantic Ocean bluefin tuna fishery acquired MSC certification, the first case for the tuna fisheries anywhere in the world. What background factors and emotions were there for these various challenges? What kind of future does he picture for the company?

──At Usufuku-honten, you spent tens of millions of Japanese yen over long years of preparation to acquire the world’s first MSC certification for Atlantic Ocean bluefin tuna fishery. I’m sure there were a number of difficult aspects of this process such as objections to your application from the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF). What feelings kept you going to go to such lengths for the MSC?

Since a while back, I have always strived for fisheries operations that don’t damage fish stock, and from the perspective of resource management, there was no need to spend tens of millions of yen and go through the ordeal of acquiring MSC certification. People say that with this certification, carrying out sustainable fishery operations gains added value and the selling prices for caught fish increase, but I don’t think the Japanese market is really at that stage yet.

In spite of all that, I still acquired the MSC, and the reason for that is that I feel adding “sustainability” to our company’s image is meaningful. MSC is recognized internationally as the top certification in the world. As the SDGs get increasing attention due to the upcoming Tokyo Olympic and Paralympic Games, I felt that incorporating this into our brand was important for strengthening our voice within the fishing industry.

Japan’s fishing industry has numerous issues. Not only the fishermen but also government officials, consumers, and other stakeholders must work together to change current conditions for the better. Amendments to current legislation and regulatory reforms are particularly essential aspects of this. By straightening myself first, I thought I would be able to get people in various positions to listen to my opinion.

I simply cannot pass the baton to my son’s generation with our fishing industry continuing in its current form. In a variety of aspects, I believe that my role is to develop Japan’s fishery into a globally-competitive industry. I mean this in the sense of achieving unbeatable quality, developing conditions that ensure solid sales, and allowing workers to shine at work. I want this industry to be one that young people will aspire to when considering their own future jobs.

──Japan’s fisheries still have a lot of issues remaining to resolve. From your perspective, what are some things you feel are especially in need of changing?

First of all, preventing illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) catch from entering our domestic markets is crucial.

Illegal tuna fishing operations are one example. Pelagic tuna fishing is thoroughly regulated by international organizations. Vessels with permission to conduct these fishing operations are noted on the white list, and unregistered vessels are prohibited from landing caught fish or distributing them.

However, there are vessels all over the world circumventing these rules, and at present, it’s easy for these fish to enter Japanese? markets. Under Japanese law, processed items are not required to display labels indicating their place of origin. There is also no law that prohibits importing of products for which the source cannot be 100% specified (as of November 2020), and for tuna processed into filets, large volumes of fish for which the catch location cannot be identified are imported.

The fish caught by IUU fishery are cheaper than those caught under strict resource management, so they enter markets in increasing numbers. As a result, no matter how strictly we manage these resources and what kind of certifications we acquire, more and more Japanese companies working sincerely to follow the rules are driven out of business, and the ratio of foreign imports further increases.

──So to eliminate IUU fishery activities, we need strict regulations that prevent this kind of catch from being sold and entering circulation. I’ve heard you also consider some aspects of aquaculture to be problematic.

Yes, I also consider excess aquaculture to be a severe problem. Catch volume around Japan is decreasing, but the reason for this is overfishing. However, coastal, pelagic and small-scale fishermen have all come together to stop overfishing, agreeing to reduce their catch volumes.

As all of these fishermen are reducing their catch, the ones continuing to carry out overfishing are major companies with purse seine and aquaculture, which continue to bring in large volumes. In coastal areas, pole and line fishing and other fishery is prohibited during spawning season.

Although “complete aquaculture” which grows juveniles from adult fish raised in captivity is being increasingly used, even in this case, the feed given to the growing fish may be fish meal which contains fish caught in the ocean. Looking at it in this way, aquaculture isn’t raising fish, but instead,

As a result, even though fish population is increasing in our areas and all over the world, more and more of them are overly lean and malnourished due to insufficient access to food. Within these caught fish, those with fatty toro are declining and lean akami fish are increasing.

Aquaculture is definitely a necessary part of fisheries. However, if people think that catching natural fish is bad and aquaculture is more environmentally friendly, this is not really the case. I consider the decline of fish stock due to excessive aquaculture to be a major problem.

Without proper management, the juveniles and the small fish used as feed for aquaculture will be depleted. Internationally as well, regulations are focused almost exclusively on larger fish, and there are few measures taken for the management of smaller fish. Thinking of these resources as a whole, I think there should be regulations to prevent overfishing of fish lower on the food chain as well. However, I have no intention of saying one side is good and the other is in the wrong. In the end, the ones who choose a side will always be the consumers. If we explain the current conditions thoroughly and allow consumers to choose, I think Japan’s distribution of seafood will change.

In addition, there are a wide range of issues in need of consideration and comprehensive initiatives, such as sharing the background of food products with consumers, loosening regulations for vessel maintenance costs, and creating a working environment that will make more young people interested in becoming fishermen for their future careers.

──Mr. Usui, you are severely concerned about current fisheries operations. When did you first develop these feelings?

I can’t say I’ve been concerned about the issues and worked for improvement since a long time ago. There was a time when I didn’t follow the rules as strictly as I do now.

Incidentally, there have been concerns about bluefin tuna disappearing from the Atlantic Ocean since about 15 years ago. To be honest, once my generation took on leadership in this industry, I was frightened about what could happen in the world. There was a need for stock management in addition to the pursuit of profit in the short term, and I worried about whether we can keep our ships staffed in spite of the decline in young fishermen.

Around that time, fishing areas were started to be managed strictly, and international management bodies took efforts to reduce the number of tuna fishing vessels. In Japan as well, measures were taken to reduce the number of these vessels and halved the number to around 600 The numbers continued to decline year by year thereafter, and there are only about 150 Japanese tuna fishing vessels still in operation now.

This has had a major impact on the fishing industry in our local area. Pelagic longline tuna fishing vessels can only land their catch in ports where there are large markets and trading companies. My vessels land their catch not only in Kesennuma but also in the ports of Shizuoka and Kanagawa.

However, the maintenance of these vessels and supplying food is all handled in Kesennuma. Pelagic fishery requires a total cost of approximately 100 million yen per vessel in upkeep costs such as, fuel, fishing gear, and food for the crew. By carrying out this spending in our local area, we support local maintenance and foodstuffs companies, and these companies can also carry out maintenance for the vessels of other fishermen outside of tuna fisheries. People sometimes say that tuna fishing vessels don’t contribute to their local community, but if any of these aspects are missing, a port town ceases its function.

When the number of pelagic fishing boats dropped, domestic ship maintenance costs surged, and increasing numbers of fishermen began taking their ships overseas for maintenance. As a result, companies in Kesennuma lost work, people started talking about them closing down. Seeing the risk in this situation, I made the decision to carry out all of the maintenance for our vessels in Japan.

It’s true that overseas can be cheaper, but quality is poor, and I decided that I’m not comfortable with leaving the precious vessels of our crew members with them and bringing our vessels to Kesennuma instead will also help save these companies. I don’t think anyone remembers that time anymore, but that was my thought process.

──In the midst of this difficult time, did you ever consider turning away from the problems, selling your vessels, or moving the headquarters overseas?

At the time, people around me said I’d be better off moving our headquarters overseas, but I never considered doing that. I wanted our operations to remain in Kesennuma as part of Japan’s proud core industries.

The “value of primary industry” is something I experienced in my 20s when I was living in Spain’s Canary Islands. As part of national policy, Europe places high value on its primary industries. This feeling is also rooted in the people’s mindsets, and people in France, Spain, Italy, and Germany all say “their country’s products are the best in the world”. Everyone takes pride in their country’s primary industries.

It actually goes further than countries, with many people saying things like “the cheese made in my region is the best in the world.” Starting from a young age, they have frequent opportunities to experience the background of their region and food culture, and everyone understands that eating local foods increases their countries’ prosperity.

On the other hand, Japanese people tend to focus on cheaper products, with many people thinking that American beef is good or European wine is good. When I consider what’s different between us and Europe, I think the relationships among neighboring countries is a factor. Within their history of conflict and invasions, the national borders have been protected not by the military but by farmers.

Farmers cultivating the land connected to preserving the nations’ holdings. I felt that this is the reason food cultivation is supported by the government.

In that case, where are Japan’s national borders? People tend to focus on land, but in Japan’s case, the true borders are the perimeter 200 nautical miles out from the shore. And when we consider who has protected these borders, in the same way as the farmers in Europe, it’s the fishermen. Rather than protecting national borders, we have protected fishing areas, preventing other countries from entering them.

However, Japan’s primary industries are all in an overall decline. Children don’t have an idea to become farmers because they can’t earn a lot of money or take pride in this kind of work, so they all leave the countryside for the cities, hoping to do something more fun. They discard their lands and hometowns, exchanging them for money and living in apartment complexes. As a result, once prosperous farmers’ areas are transformed into isolated villages of elderly residents, eventually returning to forests.

Coastal fishermen are no different. Fishing was originally the key industry for isolated islands and coastal areas. However, since it’s not that profitable, people have left their hometown and migrated to cities, and this key industry has declined.

These conditions should be stopped, cannot be allowed to continue, and we must find successors and hand over our fishery.

Because I feel this way, I have never considered giving up fishing or moving our headquarters overseas. In addition, I also had hope when the stock management and ship reductions were started. This is because I expected the price of fish to increase due to reduced supply with the catch volumes strictly managed.

However, although distribution of domestic caught fish has decreased, this gap has been filled by imports from those of overseas farmed and overfished. Farmed fish are fatty like toro all over their bodies, so they sell well in Japan. The fatty toro of natural fish fetches at a slightly higher price, but caught fish are almost entirely lean akami, so the total price per fish is lower.

Farmed fish-fed fish meal made from small fish caught in the ocean to fatten them up are more highly praised in the market. I simply couldn’t bring myself to accept that. From that time on, I started to become aware of the environmental impacts of excessive aquaculture on fish in the ocean.

──So because of those feelings, you took on a variety of different activities, and when the Great East Japan Earthquake occurred, you felt even more strongly about these issues.

That’s right. After the earthquake, I got a renewed sense of the importance of food, and I had a strong awareness of what I want to hand over for the next generation.

When the earthquake struck, the food, clothing, and shelter, essential for life were snatched away from us. However, I realized that the same clothing can be worn for several days, and even if your home is destroyed, temporary living spaces are available in gymnasiums or tents. However, there was no replacement for food. Without food to eat, it’s impossible for us to live. Without food and water, no life can survive. In those severe circumstances, I felt like I finally fully understood that.

In addition to reconstructing my town and my company, I considered myself to have another role as well, sharing what I learned from the earthquake with others, that is, the importance of food, energy, and connections with other people.

From that starting point, I began a variety of activities across industries. I am convinced that these efforts will contribute to prosperity for not only Kesennuma and our region but also Japan and the fishing industry as a whole.

──Standing at a new starting point now after acquiring MSC certification, what kind of future do you picture for your company?

This acquisition of the MSC certification at the cost of tens of millions of yen was a kind of new challenge for us. How will MSC-certified fish be received by the Japanese market? To be honest, I think it’s fine for our transaction prices to remain the same as before. If that’s what happens, it just shows the current conditions of Japan’s market.

We received numerous offers from Singapore, the United States, and Canada after acquiring the MSC certification, but there were hardly any inquiries from Japanese companies. There were some requesting discounted sales, but I have no interest in selling our fish to anyone who doesn’t properly understand their value.

If this means no one in Japan will use our fish even though we have this MSC certification, that will be a sad but acceptable result. On the other hand, if there are places that evaluate our product fairly, I think other businesses may see the value of MSC and also make the effort to certify.

Personally, I think it would be fine if certification systems disappear in the future. After all, wouldn’t it be fine for us to use the same approach as the local produce stores where farmers sell directly to consumers and put their faces on the packaging with the message “I grew this” Even if you don’t know the person, having a name included gives a sense of the handmade nature of a product, and that’s good enough.

If we can put our faces out there and take responsibility, I don’t think there’s any need for certifications. The reason certifications are needed and faces can’t be used is because people misrepresent themselves. Everyone knows that even though the prices are a little bit higher, farmers’ markets are a place to buy delicious vegetables you can eat with peace of mind. I want to behave in the same way and create a world like that.

My role at this company where I am the fifth-generation president and in my surrounding environment is to pass this on to the next generation of sons. For not only my son, but also the people who work for companies, other fishermen, and our clients, I always think about how to pass this mission on to them.

The fishing industry cannot exist with either fishermen or vessels alone. Without people who can carry out maintenance on these vessels, it all falls apart. Due to the nature of my work, I’ve had vessel maintenance performed at ports all over the world, and I feel that the skills of Japanese workers are truly quite high. We need to make sure these technical skills are also passed on to the next generation.

Vessels are a consolidation of a variety of different technologies. They must be not only built but also outfitted and continuously maintained. These vessels are the homes for crews and foodstuffs production factories. Sort of like Noah’s Ark. Ships are such precious things, we need to maintain them in peak condition, up to a level we’d be comfortable with our children and relatives riding on. I think that’s an important feeling to have. For me personally, I never allow fishermen onto ships without this peace of mind, and I think of them as vessels I’m riding on personally. I created the “Dai-ichi Shofuku-maru” with this notion in mind in collaboration with a design company.

As a ship captain, my job is to coordinate overall operations. This includes fishermen and professionals such as engine and pipe repairers. By gathering these people together and having this work completed professionally, we stimulate the economy and industry as a whole. All of that is part of a ship captain’s job.

On the other hand, I also consider myself a fisherman. As a ship captain, I am not directly involved in catching fish, but I don’t believe that fishermen are only the people who catch fish. In this industry, we need to all think of ourselves as fishermen.

We need to sustain not only fish stock and fishing but also dietary education, working environments, and the entire concept of fisheries for the next generation. I am working on all of the essential issues for this. We want to achieve sustainability, and that doesn’t mean just preserving fish. I also want to achieve sustainability for people’s lifestyles and way of life.

I will continue doing what needs to be done to achieve these goals.

Sotaro Usui

Born in 1971. After graduating from Senshu University, worked at a maritime industry company in Ishinomaki then joined the “Federation of Japan Tuna Fisheries Co-operative Associations (FJT).” In 1996, worked in the city of Las Palmas in the Canary Islands of Spain. Joined the family business, Usufuku-honten Co., Ltd., in 1997. Appointed senior managing director in 2002. Appointed 41st chairman of the Kesennuma Junior Chamber in 2009. Appointed as the current position, company’s 5th representative director in 2012. Competed in fencing during his college years and reached the Fukuoka Prefectural Universiade in 1995.

-1024x606.png)

_-1024x606.png)

1_修正524-1024x606.png)

.2-1024x606.png)

2-1024x606.png)

-1-1024x606.png)

Part2-1024x606.png)

Part1-1024x606.png)