On October 12, 2021, the MSC Fisheries Standard certification of skipjack tuna pole and line fisheries off the coasts of Kochi and Miyazaki was selected to win the Collaboration Category of the 3rd Japan Sustainable Seafood Awards. The award was given to the Japan Offshore pole and Line Tuna Fishery Sustainability Council, a group which was started in November 2019 and comprises 18 coastal skipjack tuna pole and line fishing boats belonging to the Kochi Skipjack Tuna Fishery Cooperative (Kochi Prefecture) and the Nango Fishery Cooperative (Miyazaki Prefecture).

Acquiring MSC (Marine Stewardship Council) certification comes with a heavy financial burden, which presents an insurmountable barrier for many of Japan’s independent fishermen. This project spanned multiple prefectures and fishery cooperatives, allowing small-scale fisheries to undergo inspection jointly and successfully reducing their individual financial burdens. Furthermore, this is the first example of fresh-caught skipjack tuna in Japan, and the quality of pole and line-caught fish is expected to have a large impact on the market.

We focused on the project and interviewed key members: Katsuyoshi Tanaka (head of the Kochi Skipjack Tuna Fishery Cooperative; president of Nissho LLC; and chairman of the Japan Offshore pole and Line Tuna Fishery Sustainability Council, Hisayoshi Eto (head of the Nichinan City Nango Fishery Cooperative and vice-chairman of the same council), and Makoto Suzuki (secretary general of the same council).

Japan Offshore pole and Line Tuna Fishery Sustainability Council

Created in November 2019, comprising 18 coastal skipjack tuna pole and line fishing boats: 6 from Kochi Skipjack Tuna Fishery Cooperative (Kochi Prefecture) and 12 from Nango Fishery Cooperative (Miyazaki Prefecture). They underwent MSC inspection in July 2020 and received MSC certification in June 2021.

— Congratulations on your award. Can you tell me how and why you decided to pursue the certification in this new way?

Hisayoshi Eto: Thank you very much. I think it was two years ago that Mr. Tanaka from Kochi invited me to try to acquire the MSC certification.

Many of us boat owners at Nango Fishery Cooperative were just handing the reins to our children around that time, so we wanted to join as a sort of up-front investment in our future.

Makoto Suzuki: In fact, those who practice skipjack tuna pole and line fishing have taken pride in using such a traditional fishing method for a long time. Nichinan Skipjack Tuna Pole and Line Fishery in Miyazaki was certified as a National Agricultural Heritage by the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries this February (article), and the Kochi Sustainable Skipjack Association (official site) is promoting the entire prefecture of Kochi as the “Skipjack Prefecture”. The MSC certification was only possible because there is a strong foundation of pride in skipjack tuna pole and line fishing.

The initial impetus for the project was when I met Mr. Tanaka at the Kochi Sustainable Skipjack Association (KSSA) symposium in November 2017. At the time I was at MSC, and we started talking about applying to MSC as a group. There are currently forty-some skipjack tuna pole and line fishing boats across Japan, in Kochi, Miyazaki, Mie, and Shizuoka. At first, we thought of having all of them get certified together.

Suzuki: Prior to the main MSC inspection there is a preliminary inspection which tells you what your chances are for certification and identifies any issues. To start with, we took the preliminary inspection so that individual ship owners wouldn’t have to take on the burden, and in the spring of 2019 the results came out indicating that all of us would be able to acquire certification.

When we asked everyone whether they were willing to pay to join the main inspection, some people said they would wait and see. Up to that point, a national organization called the National Coastal Skipjack/Bluefin Tuna Fisheries Association had been the point of contact, but with responses like those it could no longer act as the unifying organization. At that point, the whole thing was put on hold.

The whole thing was so disappointing that I quit MSC, went independent, and established a new organization to try for the main inspection again. At that time, Mr. Tanaka, three other ship owners from Kochi, and I visited the Nango Fishery Cooperative, as Mr. Eto just mentioned.

Katsuyoshi Tanaka: We went to tell them that Kochi wanted to do it and to ask them to join us.

Suzuki: The people at the Nango Fishery Cooperative replied, saying “We got another certification 10 years ago, but it didn’t really help us. We don’t know if MSC will work out, but we’ll give it a shot.” So a total of 18 boats, 6 from Kochi and 12 from Miyazaki, committed to going for the main inspection.

–Did the main inspection go well?

Suzuki: MSC certification takes time. We started gathering the necessary data in November 2019. Not only catch data, but bait data as well. In pole and line fishing we don’t bait our hooks, but we bait the waters to gather the skipjack tuna and get them excited before we start fishing. The bait consists of anchovies and sardines, and we gathered data on when, where, and how much of each was bought. We also gathered and submitted public information on fishery regulations and laws, resource evaluation reports, and international management frameworks.

After that, an inspector would normally come to Japan to conduct field observations, but with the coronavirus pandemic last year, the inspection was conducted online. The inspector interviewed not only the fishery cooperatives, but also researchers at the Fisheries Research and Education Agency, the Fisheries Agency, and environmental NGOs. In June 2021, we were successfully certified.

There were precedents of deep-sea fishing boats with freezers acquiring MSC certification, so the inspection was fundamentally similar, but the main point of contention in our case were the anchovies used as bait. They are only a small amount of the fish caught in Japan, but they are a scarce resource in the Pacific Ocean, and so there was concern that they were being adversely affected.

–Are there any differences between Kochi and Miyazaki?

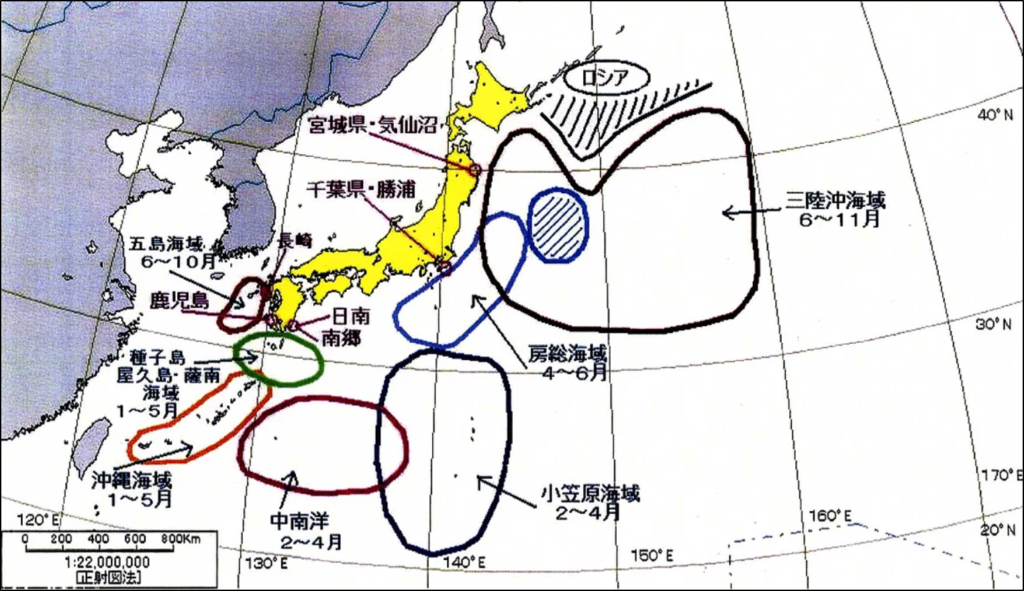

Suzuki: We fish in the same spots, so there are no differences there. Basically, coastal skipjack tuna fishing starts in February each year, and we operate near the Izu Islands and Ogasawara Islands in February and March, while the Miyazaki boats operate near the Nansei Islands. After that, the skipjack gradually migrates north, and in April and May we offload in Katsuura in Chiba. From mid-June to July and later, we fish off the Sanriku coast and offload at Kesennuma. This continues until the season when the skipjack starts to migrate back south.

The reason we choose Katsuura and Kesennuma is that there are fish brokers there who have a good eye for skipjack. Those places also become our bases of operation. We buy bait and we resupply our water and food stores, since we live on the boat during operation. If someone is sick, they can also go see a doctor. There are boathouses which provide such services to fishing boats like ours, because we can’t go back to Kochi or Miyazaki every time we need something.

–You never go home! How long do you stay aboard the boat?

Tanaka: In Kochi, we don’t go home from February to November. During that period, we’re on the boat most of the time. How about you, Mr. Eto?

Eto: We start in the Ogasawara or Okinawa Islands in February. For remote locations near Ogasawara, it takes 10 days to make one round trip. One fishing haul usually takes several days, so we don’t get back to Miyazaki often.

–If you go out fishing and there are no fish there, what do you do?

Eto: If there are no fish, we can’t go home. In fact, even if you go to a place which had fish the previous year, there’s no guarantee they’ll be there again. We continue searching for the fish until we run out of bait or fuel. We exchange information with the fishing boats from Kochi, Mie, and Shizuoka which are scattered all over as we search for the skipjack.

–You exchange information with boats from other prefectures?

Eto: We didn’t in the past, but now the four prefectures which practice coastal pole and line fishing have a “Skipjack Boat Group” on the radio. During operation, we communicate about once every three hours to update others on fish locations, so when we find them we can all hurry over. There are now fewer boats, so we have a more cooperative relationship.

Tanaka: During our heyday, Kochi had about 100 skipjack fishing boats and we had our own radio group, but now we have a joint group with other prefectures for exchanging information.

–The landscape of coastal pole and line fishing has changed, hasn’t it?

Eto: It has certainly changed in Miyazaki. When I was young, Miyazaki’s skipjack fishing did not produce fresh fish but rather fish for making dried katsuobushi flakes. The fishing grounds and offloading ports were also different. But one of the older fishermen was invited by someone from Kochi and started operating farther north near Sanriku. We followed after him and started learning how to fish for fresh fish.

We also used different boats in the past. The region we know around Okinawa has many islands, so when a storm comes in we can take shelter in the lee of an island. However, when we ventured out to Sanriku, where there are no islands, being in a small steel ship was scary. We soon learned from the Kochi fishermen to use a plastic (FRP) boat. In the beginning, we received hand-me-down boats from Kochi.

–So that’s how you became connected. Have there been any changes in Kochi?

Tanaka: Since long ago, Kochi has always done pole and line fishing for fresh fish, so our fishing methods have remained the same. The main changes have been our fishing boats getting bigger and our fishing grounds changing slightly. There was a manga titled Tosa no Ippondzuri—it’s exactly like that. What’s impressive about the fishermen from Miyazaki is that they incorporated new methods on their own, developed them, and are operating steadily. Now they have more boats than Kochi.

Eto: We only got this far thanks to everything the Kochi fishermen taught us. When we first started going north to Sanriku, all the captains around us were from Kochi. At that time, our radio codes were different, but they would write down that day’s information, seal it in an empty coffee can, and throw it overboard for us to haul up later.

-1024x606.png)

_-1024x606.png)

1_修正524-1024x606.png)

.2-1024x606.png)

2-1024x606.png)

-1-1024x606.png)

Part2-1024x606.png)

Part1-1024x606.png)